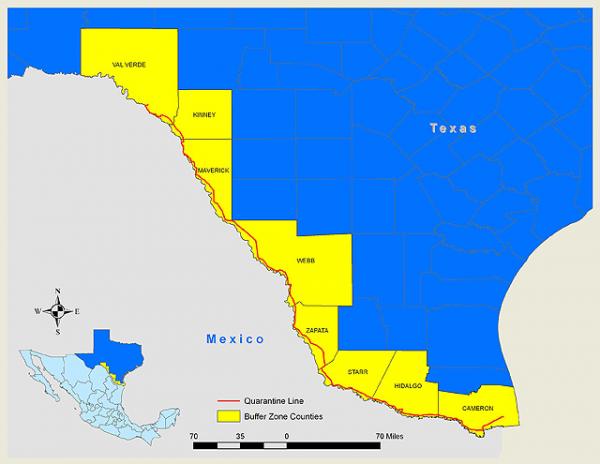

“The ticks Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) annulatus and R. (B.) microplus, commonly known as cattle and southern cattle tick, respectively, impede the development and sustainability of livestock industries throughout tropical and other world regions. They affect animal productivity and wellbeing directly through their obligate blood-feeding habit and indirectly by serving as vectors of the infectious agents causing bovine babesiosis and anaplasmosis. The monumental scientific discovery of certain arthropod species as vectors of infectious agents is associated with the history of research on bovine babesiosis and R. annulatus. Together, R. microplus and R. annulatus are referred to as cattle fever ticks (CFT). Bovine babesiosis became a regulated foreign animal disease in the United States of America (U.S.) through efforts of the Cattle Fever Tick Eradication Program (CFTEP) established in 1906. The U.S. was declared free of CFT in 1943, with the exception of a permanent quarantine zone in south Texas along the border with Mexico. This achievement contributed greatly to the development and productivity of animal agriculture in the U.S. The permanent quarantine zone buffers CFT incursions from Mexico where both ticks and babesiosis are endemic.”

Perez de Leon, AA, Teel, P. D., Auclair, A. N., Messenger, M. T., Guerrero, F. D., Schuster, G., & Miller, R. J. (2012). Integrated strategy for sustainable Cattle Fever Tick eradication in USA is required to mitigate the impact of global change. Frontiers in Physiology, 3, 195. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2012.00195.

This short review of the Tick Riders and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Cattle Fever Tick Eradication Program, will include a brief description of this vector of disease, the serious problem it posed for cattle ranchers at the start of the twentieth century, and the continuing efforts to ensure that this animal health concern is controlled.

Hammond, K. (2012). Beagle Brigade - Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.flickr.com/photos/usdagov/7880830604/

The enduring interest in the work of the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) that relies on animal-human partnerships is demonstrated by the periodic stories that appear in the popular press. A recent story in the New York Times covered the joint Department of Homeland Security’s U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and APHIS initiative nicknamed the 'Beagle Brigade.' These dogs and their APHIS handlers

“roam airport corridors to detect and intercept prohibited foods or plants that could carry diseases and wreak economic and ecological havoc on American agriculture. And with international travel returning to prepandemic levels, Hair-E [an APHIS beagle] and his colleagues are seizing an increasing number of goods outlawed from entering American soil."

Qiu, L. (2022, July 23). Meet the canine officers guarding American agriculture. The New York Times, July 24, 2022, Section A, Page 14. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/23/us/politics/beagles-airport-security.html.

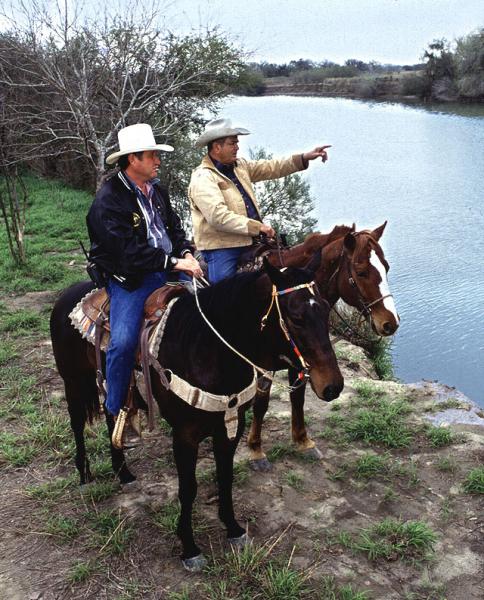

But dogs are not the only APHIS animal partners. In addition to the Beagle Brigade, the Tick Riders also protect American agriculture, but instead of food or plants hiding inside luggage, these horses and riders look out for the Cattle Fever Tick–and the potentially deadly parasites they carry–along a designated buffer zone on the southern American border.

Bauer, S. (n.d.). At the Rio Grande, Robert Rodriguez (left) and Horico Garza, of USDA's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, search for livestock that may be carrying ticks. Cattle fever ticks have been eradicated from this country since 1943 except for a narrow strip along the border. Image Number K5439-20. Agricultural Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.ars.usda.gov/oc/images/photos/k5439-20

What is Bovine Babesiosis or Cattle Fever?

“Bovine babesiosis is a tick-borne parasitic disease that results in significant morbidity and mortality in cattle. The economic losses can be considerable, especially when animals with no immunity are moved into an endemic area. Three species of Babesia cause most clinical cases in cattle: Babesia bovis and B. bigemina are widespread in tropical and subtropical regions, while B. divergens circulates in parts of Europe and possibly in North Africa. Bovine babesiosis can be managed and treated, but the causative organisms are difficult to eradicate. The United States eradicated B. bovis and B. bigemina from most of the country by eliminating its tick vectors in an intensive campaign that took 40 years. Currently, these ticks persist only in a quarantine buffer zone between the U.S. and Mexico. Reintroduction is a significant threat; the tick vectors have been detected periodically outside this buffer zone, and acaricide resistance is a growing issue for control. Most cattle Babesia do not seem to affect humans; however, B. divergens can cause rapidly progressing, life-threatening hemolytic anemia in people who have had splenectomies.”

Spickler, A.R. (2018). Bovine Babesiosis. College of Veterinary Medicine. Iowa State University. https://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/bovine_babesiosis.pdf.

Bovine babesiosis is a serious disease that has been described as commonly presenting with

“liver and kidney failure due to hemolysis with icterus, hemoglobinuria, and fever. Acute encephalitis is a less common presentation and begins acutely with fever, ataxia, depression, deficits in conscious proprioception, mania and convulsions, and coma. The encephalitic form generally also has a poor prognosis. Sudden death may also occur.”

Underwood, W.J., Blauwiekel, R., Delano, M.L., Gillesby, R., Mischler, S.A., & Schoell, A. (2015). Biology and diseases of ruminants (sheep, goats, and cattle). In Fox, J.G., Anderson, L.C., Otto, G.M., Pritchett-Corning, & Whary, M.T. (Eds.) Laboratory Animal Medicine, third edition, pp. 623-694. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-409527-4.00015-8.

Garry adds these insights,

“Babesiosis is a protozoan disease of cattle that has been eradicated from the United States thanks to control of the causative ixodid ticks. The disease is also called Texas fever, redwater, piroplasmosis, or tick fever in cattle. Babesiosis may be caused by six or more species of Babesia that are divided morphologically into large or small types. The major large species is Babesia bigemina, and the major small species is Babesia bovis. The disease is seen primarily in tropical and subtropical climates but remains a threat to the United States from Central America and Mexico.”

Garry, F. (2008). Miscellaneous infectious diseases. In Divers, T.J. & Peek, S.F. (Eds.), Rebhun’s Diseases of Dairy Cattle, second edition, pp. 606-639. Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4160-3137-6.X0001-5.

This excerpt breaks down the profound impact of this disease into material effects:

"The southern cattle tick, Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus, is a highly adaptable ectoparasite that has become established in nearly all tropical and subtropical regions of the world where domesticated cattle production occurs. This tick species is a major problem for livestock production worldwide because it is the biological vector for disease agents causing bovine babesiosis (Babesia bovis, B. bigemina) and anaplasmosis (Anaplasma marginale). Along with the closely related cattle tick (R. annulatus) it was likely introduced to the New World by Spanish colonialists. By 1906, economic losses were estimated to be > $130 million per year in the U.S. alone; this would be the equivalent of > $3 billion today. The Rhipicephalus-Babesia system was one of the first vector-borne diseases to be described in detail, which led to the insight that eradicating tick vectors would prevent the spread of bovine babesiosis. Consequently, the National Cattle Fever Tick Eradication Program (CFTEP) was established in the U.S. in the early 1900s to eradicate both Rhipicephalus species (collectively referred to as cattle fever ticks) from 14 southeastern states and southern California. By 1943, both species were successfully eliminated from most of the U.S., with the exception of southern Texas and Florida. Complete eradication in Florida took another 17 years [3,6] because the ticks successfully used white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus; hereafter WTD) as an alternative host and central Florida contains highly suitable habitats for cattle fever ticks. Complete eradication may never have been achieved in some areas along the Texas border with Mexico, and tick infestations in this area have been reported yearly since 1960."

Busch, J. D., Stone, N. E., Nottingham, R., Araya-Anchetta, A., Lewis, J., Hochhalter, C., Giles, J. R., Gruendike, J., Freeman, J., Buckmeier, G., Bodine, D., Duhaime, R., Miller, R. J., Davey, R. B., Olafson, P. U., Scoles, G. A., & Wagner, D. M. (2014). Widespread movement of invasive cattle fever ticks (Rhipicephalus microplus) in southern Texas leads to shared local infestations on cattle and deer. Parasites & Vectors, 7, 188. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-188.

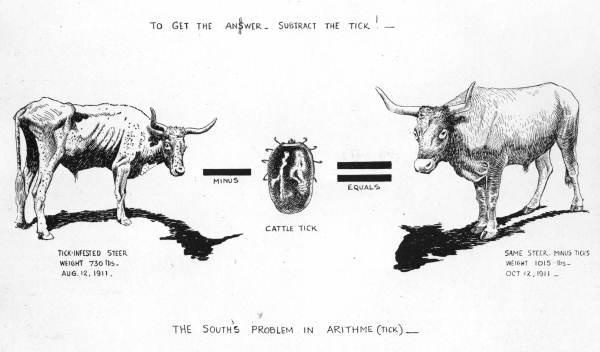

Effects of ticks on cattle (1913). Florida Memory. State Library and Archives of Florida. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/1357.

What is the Cattle Fever Tick?

Swiger, S.L. (2017). Cattle Fever Ticks. Texas A&M AgriLife Extension. https://agrilifelearn.tamu.edu/s/product/cattle-fever-ticks/01t4x000004OUc7AAG

“[I]t is evident that the most complete knowledge of the habits and life history of the tick is of the utmost importance. All means of eradication must depend upon such knowledge, and improvements in present methods must depend upon additional information regarding the tick. Dr. Cooper Curtice…has written as follows: ‘To the scientist studying the tick to learn its life history, habits, form, and anatomy, the fact’ that these animals are pests to the stockman throughout the greater part of the year is of very little importance, while the latter care little about such matters if he can only learn how to rid his cattle of them. Yet it is only by learning the life history that remedies to prevent them can be applied intelligently, and the fact that the knowledge attained is of practical value adds a double interest to their study.” pp. 9-10

Hunter, W.D. & Hooker, W.A. (1907). Information concerning the North American fever tick: With notes on other species. Bureau of Entomology. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Bulletin Number 72. https://archive.org/details/informationconce72hunt.

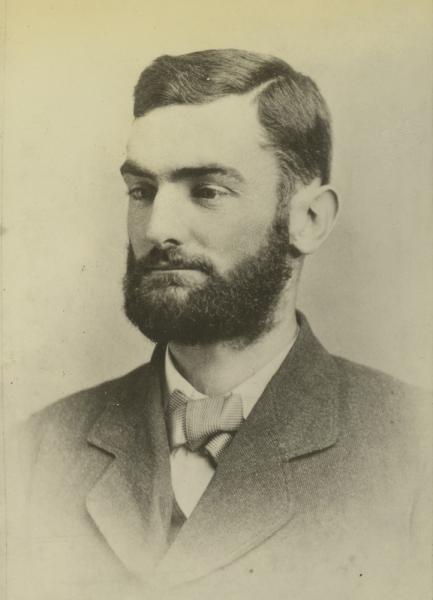

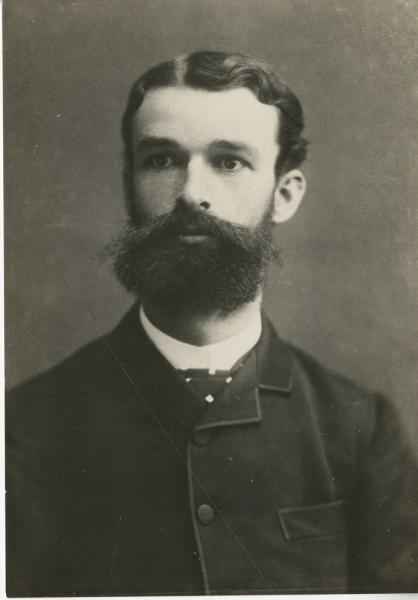

The National Agricultural Library’s Special Collections has a discussion of how the cattle fever tick came to be identified as a vector of disease by scientists from the USDA Bureau of Animal Industry like the aforementioned Cooper Curtice, as well as Frederick L. Kilborne and Theobald Smith. You can review the section on Texas Cattle Fever in their USDA’s Contributions to Veterinary Parasitology exhibit.

Cooper Curtice

Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, U.S. Department of Agriculture

https://www.nal.usda.gov/exhibits/speccoll/exhibits/show/parasitic-diseases-with-econom/item/8292

Frederick L. Kilborne

Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, U.S. Department of Agriculture

https://www.nal.usda.gov/exhibits/speccoll/exhibits/show/parasitic-diseases-with-econom/item/8199

Theobald Smith

Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, U.S. Department of Agriculture

https://www.nal.usda.gov/exhibits/speccoll/exhibits/show/parasitic-diseases-with-econom/item/8205

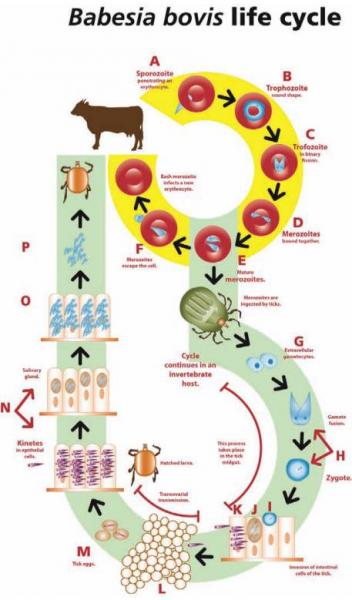

The life cycle of Babesia bovis and the Cattle Fever Tick

The life cycle of Babesia bovis from Mosqueda, J., Olvera-Ramirez, A., Aguilar-Tipacamu, G., & Canto, G. J. (2012). Current advances in detection and treatment of babesiosis. Current Medicinal Chemistry, 19(10), 1504–1518. https://doi.org/10.2174/092986712799828355.

Figure used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/)

Mosqueda, Olvera-Ramirez, Aguilar-Tipacamu, and Canto (2012) map out the steps of the Babesia bovis life cycle. “The protozoan parasite Babesia bovis [is] a causative agent of bovine babesiosis” and is transmitted by ticks to cattle (Levy & Ristic, 1980).

- Babesia bovis sporozoite invades an erythrocyte and transforms into a trofozoite.

- The trofozoite in a ring shape.

- Two merozoites are generated from each trofozoite by binary fission.

- Merozoites are initially bound together resembling two pears in an acute angle.

- The mature merozoites separate before escaping the erythrocyte.

- Merozoites are liberated from the erythrocyte. Some of them will invade new erythrocytes and develop into trofozoites, while others will be picked up by adult ticks to continue their cycle in the invertebrate host.

- Sexual stages are freed from the red blood cells in the intestinal tick lumen and develop to gametocytes.

- The gametocytes transform into male and female gametes that form a zygote after fusion.

- The zygote develops into an infecting stage and penetrates the tick intestinal cells.

- Fission bodies form and from them motile kinetes develop.

- Kinetes destroy the intestinal cells, escape into the haemolymph and distribute into the different cell types and tissues, including the ovaries.

- In the ovary, embryo cells are infected by kinetes (transovarial transmission).

- When the female tick lays her eggs, the embryos are already infected.

- Hatched infected larvae attach to a bovine and the kinetes migrate to the salivary glands of the tick, where they form a sporoblast.

- Thousands of sporozoites develop from each sporoblast.

- Tick larvae feed from the bovine blood and the sporozoites are liberated with saliva into the animal’s circulatory system.

Centers for Disease Control. Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria (DPDM) (2017). Ticks. DPDx – Laboratory Identification of Parasites of Public Health Concern. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/ticks/index.html.

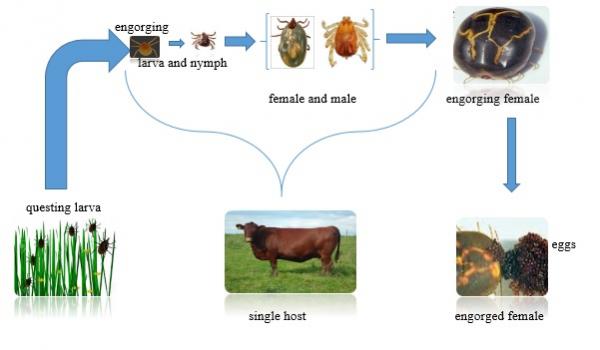

The Centers for Disease Control provide another perspective when they describe the lifecycle of the tick itself.

“One-host ixodid ticks remain on the same host for the larval, nymphal and adult stages, only leaving the host prior to laying eggs. Vertical transmission of Babesia via transovarial transmission has been demonstrated for some species of ticks. Gravid females lay eggs in the environment

. The eggs hatch into six-legged larvae

. Larvae seek out and attach to the host and after two molts, develop into adults

–

. Although humans may serve as incidental hosts for species normally found on other animals, they usually do not host all three stages. Females drop from the host to lay eggs

and the cycle repeats” (2017).

Finally, Nyangiwe, Yawa, and Muchenje (2018) provide a useful graphic illustrating how the cattle fever tick follows a “one-host lifecycle,” whereby the “ticks remain on the same host for the larva, nymph and adult stages, leaving the host only prior to laying eggs.”

Lifecycle of the one-host tick

Nyangiwe, N., Yawa, M., & Muchenje, V. (2018). Driving forces for changes in geographic range of cattle ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) in Africa: A review. South African Journal of Animal Science, 48(5), 829-841. http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/sajas.v48i5.4. Figure is used under the terms of the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 South African License.

The Means of Transmission

“In the whole list of diseases affecting the domesticated animals, there is none so peculiar in its character or so mysterious in its phenomena as was this one previous to these researches. The dissemination of of the deadly contagion by apparently health cattle, and the harmlessness in general of the really sick animals were inexplicable by any facts which were furnished by the study of other diseases. Veterinarians who had not had an opportunity to observe this disease were skeptical in regard to the correctness of such conclusions, and some spoke of them as a ‘romance in pathology.’ These early observations have not only been confirmed. But the phenomena have been explained, and our knowledge placed upon a scientific basis.” p. 7

Smith, T. & Kilborne, F.L. (1893). Investigations into the nature, causation, and prevention of Texas or southern cattle fever. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Bureau of Animal Industry. Bulletin Number 1. https://archive.org/details/bullbai001.

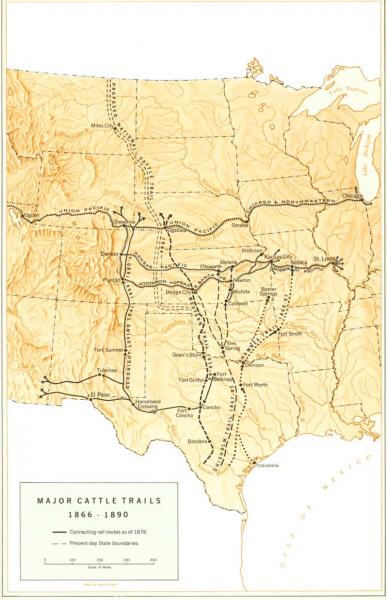

Since Bovine Babesiosis was transmitted among cattle indirectly through the vector created by these one-host ticks, neither the disease’s cause nor its means of control were readily apparent. The seriousness of the problem became impossible to ignore, however once animals from the south were transported to the midwest and north and Bovine Babesiosis started to spread.

"Before the Civil War, southern cattle were often considered ‘scrawny’ or lean compared with those in the north. Once the cattle drives from Texas to the north began, the reason for this became clear, as northern cows started to fall ill after mingling with southern herds. Symptoms for affected cows included increased basal temperature, pulse, and respiration; loss of appetite; and in some cases, hemoglobinuria for a duration of eight to 10 days. Mortality rates for northern cattle were as high as 90%, giving rise to legitimate fear of what soon became known as Texas fever.

States quickly outlawed Texas cattle drives across their borders and instituted quarantines against the Texas herds, jeopardizing the entire industry if a solution could not be found."

Emrich, J.S. & Richter, C. (2018). A brief history of bovine immunology in Texas. American Association of Immunologists Newsletter, March/April, 62-65. https://www.aai.org/About/History/History-Articles-Keep-for-Hierarchy/A-Brief-History-of-Bovine-Immunology-in-Texas.

National Park Service (1980). Major cattle trails 1866-1890. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cattle-trails.jpg

“Between 1860 and 1870, the population of the United States (especially in northern cities) grew 22 percent. In the same period, the number of cattle decreased seven percent, meaning that demand outstripped supply, which elevated market prices for beef. To tap this lucrative opportunity, America’s first big business was invaluable to cattlemen. Transcontinental railroads conveniently matured after the Civil War, and encouraged the movement of long-neglected Texas herds because they united frontier regions with huge supply centers….

Moving cattle to fledgling Midwestern cow-towns was long, hard, and debilitating. The drives were hailed as the “greatest migrations of domestic animals in history,” and were hundreds of miles long….

The northwardly-bound droves transmitted a mysterious disease to herds they came in contact with. Lone-star shipments shared pastures before being slaughtered, and within days of their departure, local herds were infected. Strangely, longhorns were immune to the disease, but the ailment killed other Midwestern cattle at astonishing rates. In 1866, ranchers in Kansas and Missouri staged grassroots protests to prevent droves from entering their states. In the following year, the Kansas and Missouri legislatures prohibited Texas cattle from certain counties. Although the Texas cattle drives were transforming the American frontier, uneasiness surrounded this vexing ailment.” p. 10-12

Erlandson, E.M. (2012). Cattle plague in NYC: The untold campaign of America’s first board of health, 1868. Unpublished manuscript. http://hdl.handle.net/1794/12138.

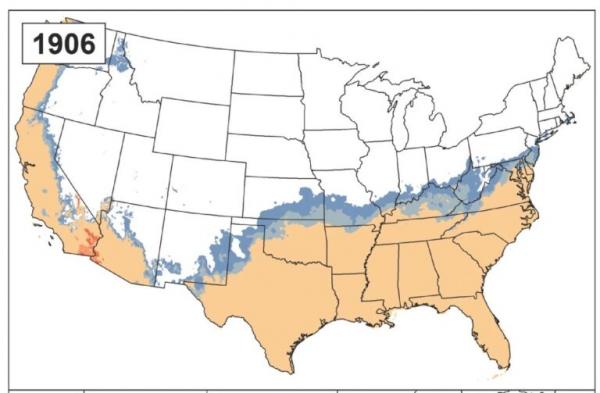

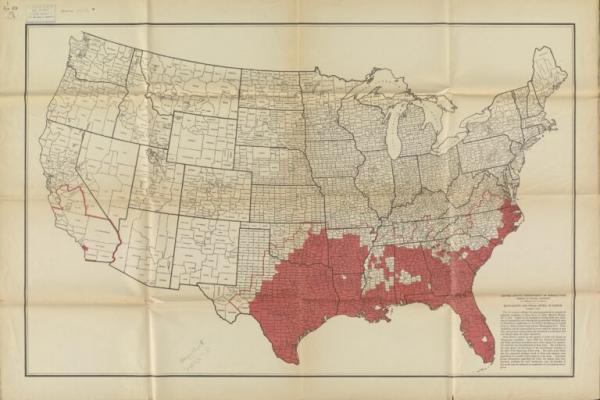

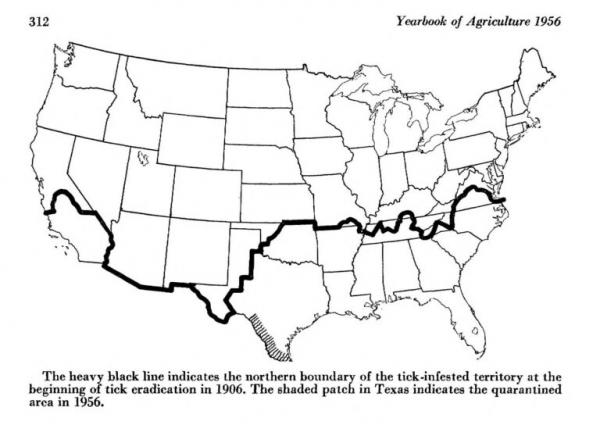

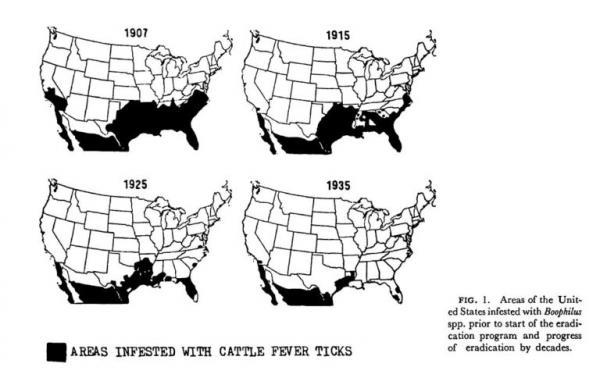

Mapping the Outbreak

These maps illustrate several of the most important geographical variables related to this outbreak: the distribution of cattle fever ticks, the disease Bovine Babesiosis itself, and the quarantine area imposed by the Bureau of Animal Industry on December 1, 1915.

Model prediction for Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) annulatus for 1906. Adapted from Giles, J.R., Peterson, A.T., Busch, J.D., Olafson, P.U., Scoles, G.A., Davey, R.B., Pound, J.M., Kammlah, D.M., Lohmeyer, K.H., & Wagner, D.M. (2014). Invasive potential of cattle fever ticks in the southern United States. Parasites & Vectors, 7, 189. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-189. Used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)

Bureau of Animal Industry (1915). Quarantine for Texas fever of cattle: December 1, 1915. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://archive.org/details/CAT31412086.

Map showing tick infestation in the United States in 1906. Cole, T.W. & MacKellar, W.M. (1956). Cattle Tick Fever. In Stefferud, A. (Ed.). The Yearbook of Agriculture 1956: Animal Diseases, pp. 310-312. https://archive.org/details/yoa1956

Areas of the United States infested with Boophilus spp. prior to the start of the eradition program and progress of eradication by decades. Graham, O.H. & Hourrigan, J.L. (1977). Eradication programs for the Arthropod parasites of livestock. Journal of Medical Entomology, 13(6), 629–658. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/13.6.629

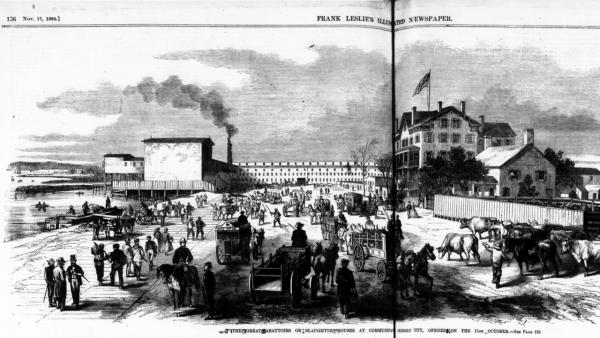

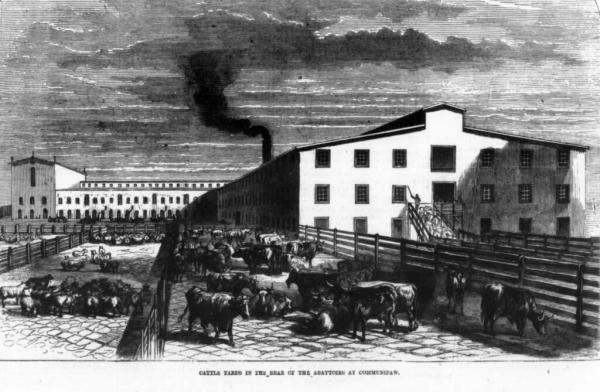

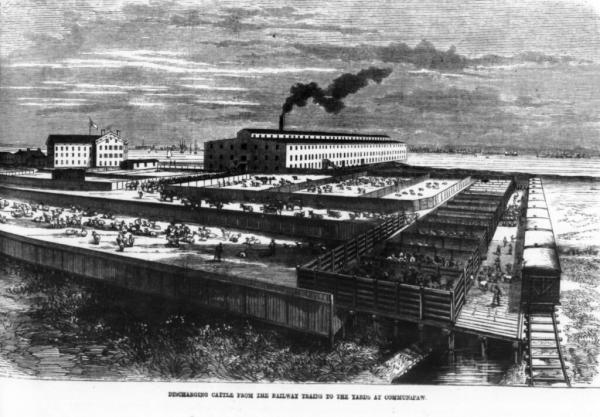

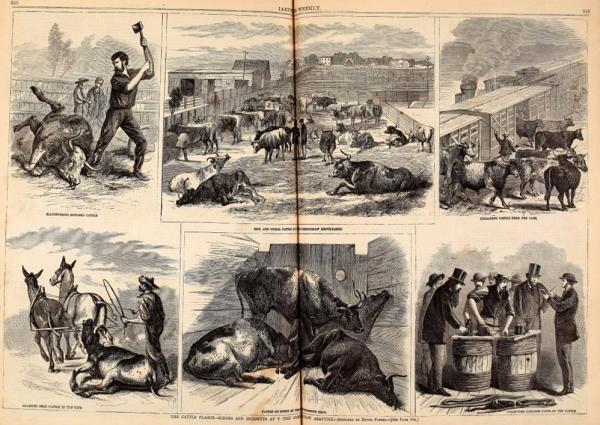

Concern in New York & New Jersey: The Communipaw Abattoir

It did not take long for the disease to spread northward from Texas and other southern locations. The results were very serious and both government and industry sounded the alarm. A particularly noteworthy incident occurred in a newly opened facility in Communipaw, New Jersey.

“When reports were received on August 8, 1868, that several carloads of cattle with Texas fever had arrived in the cattle yards of New Jersey, the board investigated and discovered that over 50 percent of the cattle had died during shipment. The president of the board immediately telegraphed the governors of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York asking them to inspect all cattle passing through their states enroute to New York City. In addition, quarantine yards were established in the city to check on all incoming cattle.” p. 38

Duffy, J. (1974). A history of public health in New York City: 1866-1966. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

“In 1868, Texan cattle shipped up the Mississippi River to Cairo and thence by rail into Illinois and Indiana early in June caused during the summer of that year enormous losses of cattle in these States. Moreover the East began to be aroused because Western cattle infected with the disease had been shipped eastward for beef and were dying of Texas fever on the way, in the New York stock yards and elsewhere. The question as to the effect of such diseased flesh upon human health was at that time entirely new and caused much uneasiness. The cattle commissioners of New York State and the board of health of New York City made a vigorous effort to check the importation of diseased cattle from the West, and to their efforts we owe much valuable information of this disease.” p.12

Smith, T. & Kilborne, F.L. (1893). Investigations into the nature, causation, and prevention of Texas or southern cattle fever. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Bureau of Animal Industry. Bulletin Number 1. https://archive.org/details/bullbai001

The Great Abattoirs or Slaughterhouses at Communipaw, Jersey City, Opened on the 15th October (1866). Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, November 17, XXIII Number 581, 136-137. https://archive.org/details/sim_leslies-weekly_1866-11-17_23_581.

In response to the effects of having live animals being driven through the streets of New York City, the city’s health board began to institute regulations restricting how they could be transported and where they would be slaughtered. In response to these changes, several large slaughterhouses, or abattoirs were constructed outside of large urban centers, away from consumers and closer to the cattle transported from Texas to the north via railroad. This was seen as an improvement.

“…the whole work of slaughtering and preparing for market is arranged to be done by machinery, thus economizing time, labor, and expense, and the facilities for throwing the product of the great slaughter-houses into market in good order are only excelled by the arrangement which brings the unslaughtered cattle from the Central Railroad cars to the place of their wholesale immolation. Added to all this, the grounds include an excellent hotel for drivers and others interested, and trying-houses for offal, tallow and lard, giving promise that one of the worst nuisances of the crowded city will soon be carried totally beyond its limits. It might be too much to say that the boast of the Yankee of his ‘mutton-machine,’ by which a sheep, thrown in, was immediately turned out in the shape of four quarters of roast mutton, a wool hat, a leather apron and a gross of bone buttons, is here exceedingly carried into effect; but certainly the celebrity of Cincinnati arrangements for hog-killing is imperiled from the completeness of the Communipaw cattle slaughtering arrangements, and this when enterprise is really on only its beginning.” p. 135

The great abattoirs at Communipaw (1866). Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, November 17, 1866, XXIII Number 581, 135. https://archive.org/details/sim_leslies-weekly_1866-11-17_23_58.

Illustrations by Edwin Forbes from “The Cattle Plague.” Harper’s Weekly, August 29, 1868, XII, Number 609, 552-553. https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv12bonn.

The New York City government struggled to respond to these horrific conditions documented by the press and eventually instituted a series of measures that contained the outbreak of Texas Cattle Fever and improved conditions at Communipaw.

“The fledgling Board of Health had defeated an unfamiliar and formidable public health issue by slaughtering exposed livestock, instituting rigid quarantines, disinfecting stock yards and railcars, regulating transportation, patrolling meat markets, meticulously examining new cattle shipments, collaborating with other states, and cracking down on the business of slaughtering in New York City." p. 54

Erlandson, E.M. (2012). Cattle plague in NYC: The untold campaign of America’s first board of health, 1868. Unpublished manuscript. http://hdl.handle.net/1794/12138.

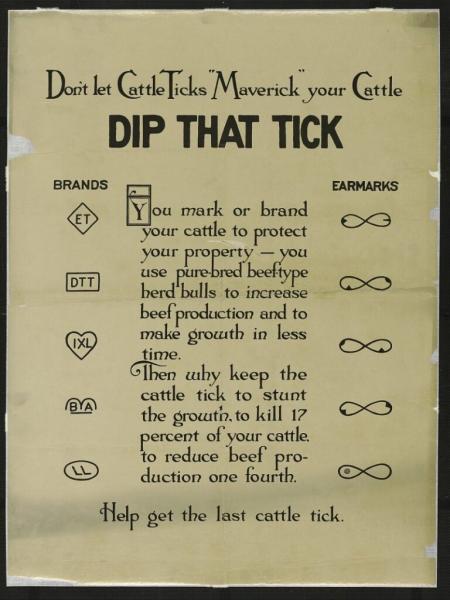

Controlling the Outbreak: “Dip That Tick!”

“Cattle ticks existed in Europe, Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Australia, but until 1906 nobody has seriously embraced eradication on a continental scale. The scientific and political obstacles were simply too imposing. To overcome private coordination failures, clearing cattle ticks from the United States required the massive application of government police power that affected the day-to-day activities of millions of farmers and extensively regulated intrastate and interstate trade. The Bureau of Animal Industry (BAI) launched a coordinated national vector-eradication campaign on 1 July 1906. The Bureau’s tick program extended to fifteen states, segregating much of the south and part of California….The success of the campaign against Texas fever required new science, new laws, and new constitutional interpretations. As great as the BAI’s scientific advances were, its public policy achievements were the major story. The principal challenges were to build cooperative arrangements with the states, to educate and secure the cooperation of the public, and, when necessary, to deploy federal and state police to control the destructive behavior of resisters. The program swept the cattle ticks and the disease-carrying protozoa they carried from the nation by methodically quarantining areas, dipping livestock repeatedly, and then protecting cleansed areas from reinfection. In the process, this campaign created a public good—a vector-eradication model that would be used in the global fights against parasites and the disease they carry." p. 251; 275

Olmstead, A.L. & Rhode, P.W. (2015). Arresting contagion: Science, policy, and conflicts over animal disease control. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

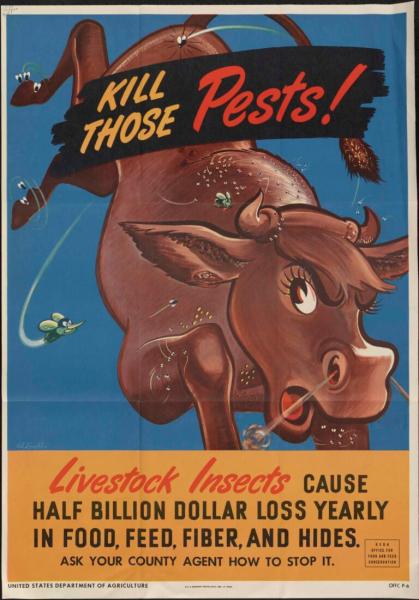

Over the course of several decades, the U.S. Department of Agriculture carried out efforts to (1) alert cattle owners about the dangers of cattle ticks and the need for preventative action, (2) enforce a quarantine area, and (3) demonstrate the best ways to address the situation. These two posters illustrate how these risks were communicated to the public: one from the first effort to control the outbreak and the second from 1948, after the cattle tick was eradicated from the United States, excluding the current quarantine “buffer zone,” patrolled by the APHIS Tick Riders.

Dip that tick (n.d.). National Museum of American History. The Smithsonian Institution. Record ID: nmah_502069. https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/object/nmah_502069.

Loughlin, E. (1948). Kill those pests! Livestock insects cause half billion dollar loss yearly in food, feed, fiber, and hides: Ask your county agent how to stop it. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://archive.org/details/CAT31069222

On December 1, 1915 a quarantine area was imposed by the Bureau of Animal Industry to limit the spread of the outbreak. While a map delineating this area appears above, these photographs document the work of the inspectors charged with enforcing the quarantine.

Hillers, J.K. (1929). St. Mary’s River Bridge on U.S. 17 at Georgia-Florida state line: Cattle tick quarantine inspector at work. Department of Commerce. Bureau of Public Roads. National Archives and Records Administration. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/205739448

Hillers, J.K. (1929). St. Mary’s River Bridge on U.S. 17 at Georgia. Florida State line. Cattle tick and Mediterranean fruit fly quarantine crew at work. Department of Commerce. Bureau of Public Roads. National Archives and Records Administration. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/205739446

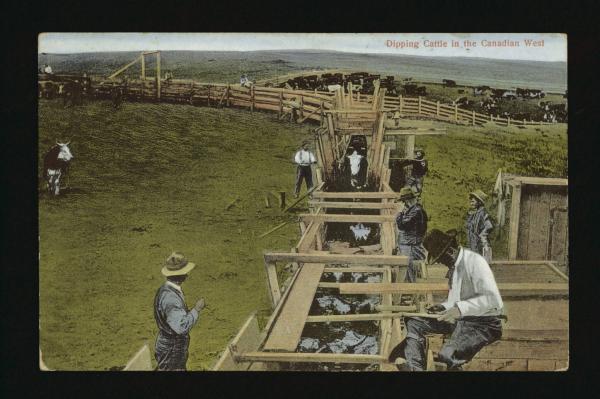

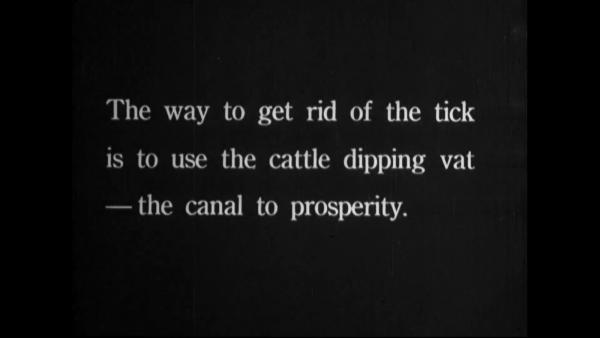

The Cattle Dip: The “Canal to Prosperity”

Rumsey & Company (1910). Dipping vat at Circle Ranch, near Queenstown, Alberta. https://archive.org/details/PC009898

“By the term cattle dipping is meant the immersion of cattle in solutions of various chemical preparations for tlie purpose of destroying parasites which infest their skin. The purpose of this paper is to consider the practice of cattle dipping, with particular reference to freeing the cattle of the parasites known as ticks, especially…the tick which causes Texas, or Southern, fever." p. 453

Norgaard, V.A. (1899). Cattle dipping, experimental and practical. In Yearbook of the United States Department of Agriculture 1898, pp. 453-472. United States Department of Agriculture. https://archive.org/details/yoa1898/page/453.

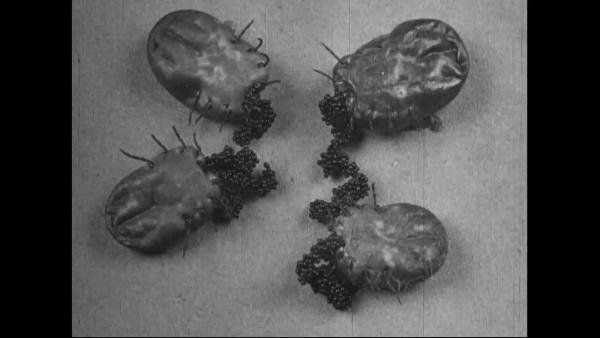

Tidwell, J. (n.d.). Female cattle ticks preparing to lay eggs. These ticks can transmit serious diseases to cattle. Image Number D3532-1. Agricultural Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.ars.usda.gov/oc/images/photos/jan16/d3532-1/

Norgaard, V.A. (1899). Cattle dipping, experimental and practical. In Yearbook of the United States Department of Agriculture 1898, pp. 453-472. https://archive.org/details/yoa1898/page/453

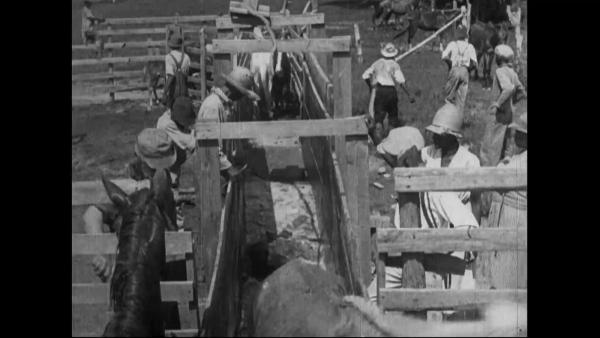

In large part, the success of the 1906 initiative relied upon the use of what came to be known as the “Cattle Dip” to kill the ticks that were the carriers of Bovine Babesiosis. This process required that each animal pass through a solution that would effectively kill any ticks that they might carry. It needed to be done repeatedly, using the proper materials, within facilities that were constructed to meet the required specifications.

Fritz, A.L. (2014). This is the dip vat used to treat Mexican cattle for cattle fever ticks to prevent their spread into the U.S. at the newly built U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Animal Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) Livestock Contingency Inspection Facility along the Mexican border in Douglas, AZ. https://www.flickr.com/photos/usdagov/15581737481. Used under conditions of the Attribution 2.0 Generic License (CC BY 2.0). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Bauer, S. (2002). After a 36-year campaign, cattle fever ticks were finally declared eradicated from the United States in 1943. Today, the only remaining area where these ticks are found is a narrow strip of land along the Texas-Mexico border that has been quarantined since 1938. These cattle are going through a tick treatment bath at an APHIS facility in McAllen, Texas. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cattle_tick_treatment.jpg

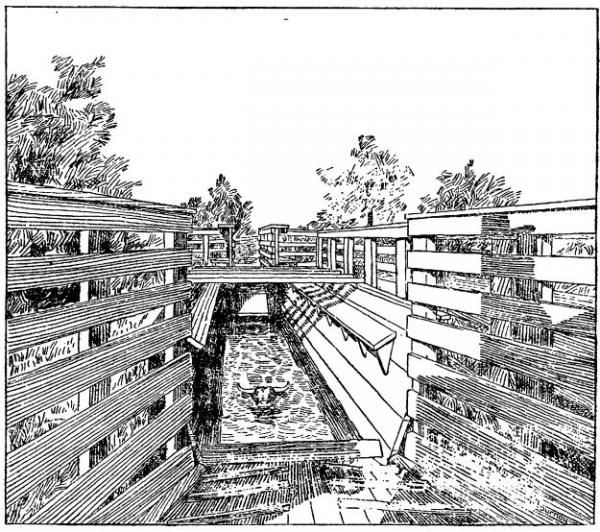

Temple Grandin's Cattle Dipping Vat (CDV) Design

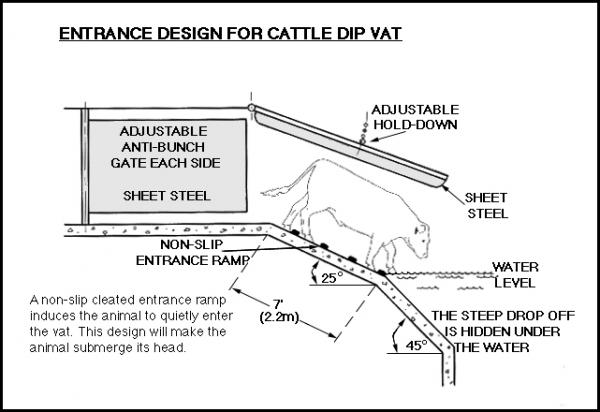

The researcher and advocate for people with Autism, Temple Grandin, describes her viewpoint on cattle dipping vats (CDV):

“Throughout the world, there is a renewed interest in cattle dip vats (plunge dips) to kill external parasites. To be effective, the animal must be completely submerged. The advantage of this design is that it encourages the animal to become fully submerged. It also reduces splashing because the adjustable hold down prevents wild leaping. Reducing splashing also reduces the risks of chemicals getting on people.

The ramp has a nonslip surface and the animal walks down it. It is NOT a slide. Do NOT make a slide. The 25 degree angle of the ramp orients the animal’s center of gravity towards the water, and there is a steep drop off at the end of the ramp that is hidden under the water. When the entering animal steps off the end of the 25 degree ramp, it falls in. The cattle keep moving forward because the ramp appears to continue into the water. With this design, it is possible to eliminate the use of poles to force the heads of the animals under the water. When the animal steps out over the seep drop off, it falls in.

To prevent drowning, only one animal should enter the vat at a time. Animal entry can either be controlled with a sliding gate or an anti-bunch gate. The two anti-bunch gates are positioned to narrow the entrance so that only one animal can enter at a time.”

Grandin, T. (n.d.). Explanation of dip vat entrance design. https://www.grandin.com/design/blueprint/enter.dipvat.html.

Grandin’s piece includes her design for a CDV entrance.

USDA Cattle Dipping Vat Designs

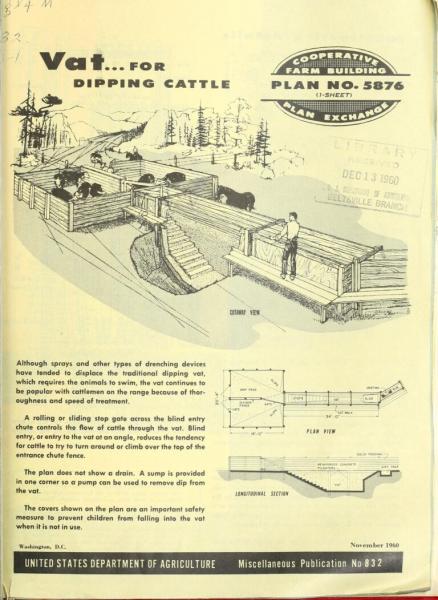

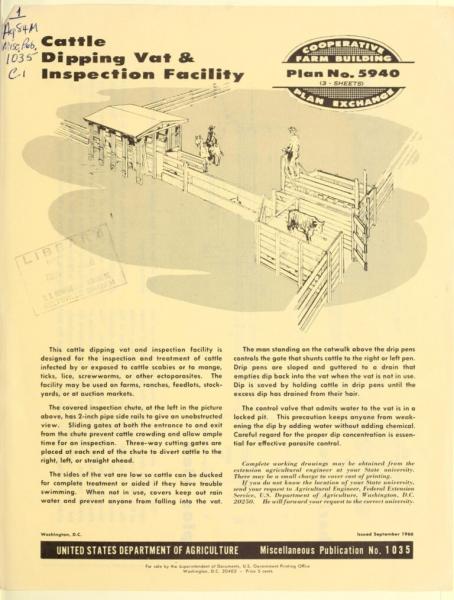

There were also U.S. Department of Agriculture publications to help cattle farmers with building plans for CDVs, published both at the time of the outbreak and significantly later.

Graybill, H.W. (1911). Directions for constructing a vat and dipping cattle to destroy ticks. Bureau of Animal Industry Circular 183. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://archive.org/details/CAT31283812

U.S. Department of Agriculture (1960). Vat for dipping cattle. Miscellaneous Publication Number 832. https://archive.org/details/vatfordippingcat832unit

U.S. Department of Agriculture (1966). Cattle dipping vat & inspection facility. Miscellaneous Publication Number 1035. https://archive.org/details/cattledippingvat1035unit

[President] William Howard Taft Watching a Cattle Dipping (1909). Oklahoma Historical Society: The Gateway to Oklahoma History. https://gateway.okhistory.org/ark:/67531/metadc230806/m1/1/?q=taft

The “Federal Filmmakers” of the U.S. Department of Agriculture

The USDA employees fighting the Cattle Fever epidemic used all available tools to spread their message about the urgent need for action to limit the effects of the disease and to eliminate its spread. Aside from printed materials, the employees of the Bureau of Animal Industry created, showed, and distributed films that some credit with having an impact on the Cattle Fever Tick outbreak.

"Interestingly, The Charge of the Tick Brigade and a related live-action film titled Mollie of Pine Grove Vat, also about tick eradication, may have been among the first motion pictures seen by some rural southern audiences. Years later a report from an MPS [Motion Picture Service] staff member claimed that ‘thousands of persons . . . in the hinterland districts of the South will remember this [Mollie of Pine Grove Vat] as the first motion picture they ever saw, as the . . . motion picture truck carried [it] to many remote communities where commercial films had never been seen.’ The USDA considered these two motion pictures crucial to the success of the tick eradication effort because it believed that the films had been able to win over opponents of the USDA’s campaign." p. 6

Winn, J.E. (2012). Documenting racism: African Americans in US Department of Agriculture documentaries, 1921-42. New York: Continuum.

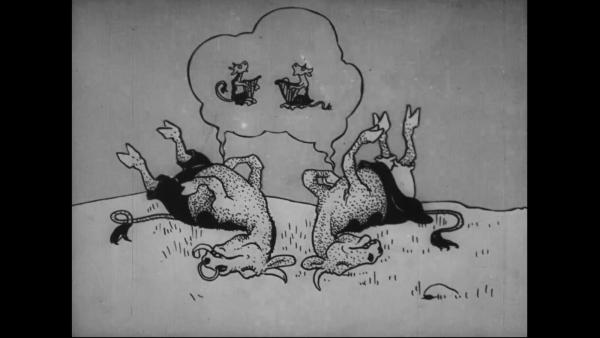

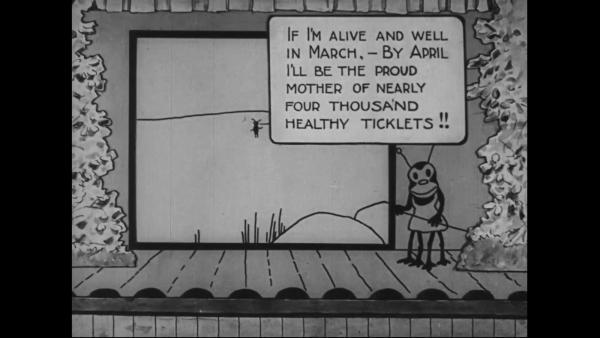

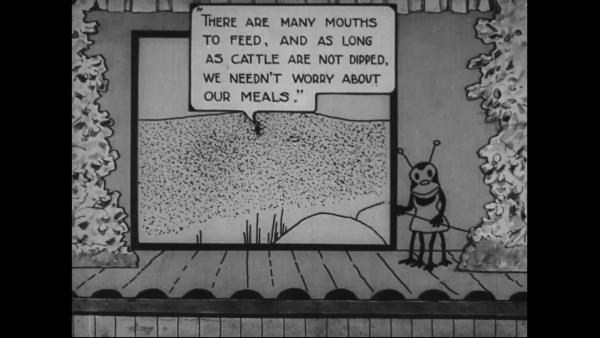

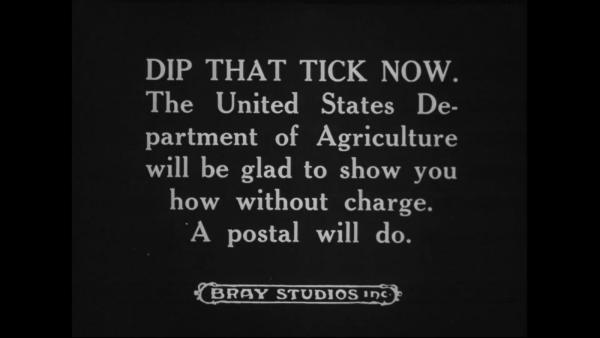

The Charge of the Tick Brigade

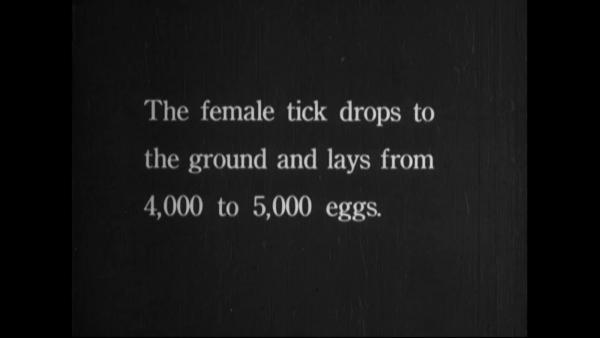

"Aiming the eradication campaign at the broadest possible audience, the USDA commissioned Bray Studios to produce an animated film, The Charge of the Tick Brigade (1919). Written by Max Fleischer shortly before he gained notoriety for the Out of the Inkwell series, this one-reel cartoon (running approximately seven minutes) gives a humorous account of a naïve cow couple that unwittingly suffers the deadly attack of a sneaky ‘brigade’ of tick thugs. After being tricked by the tick ringleader into fetching her husband to defend her honor, the wife-cow flees in horror, as she and her husband are pursued by a previously hidden army of ticks that has rapidly descended on their pasture….After infestation, both cows decline and die in exaggerated fashion over the course of a short montage, which concludes with an image of little cow angels playing harps over their corpses….In the second act, the intertitles offer a statistical analysis of the life cycle of the cattle tick, and then cede the stage to an animated mama-tick who screens a brief film about her prolific family tree. This film-within-the-film uses simple animation to visualize the amazing reproductive capacities of a single female tick. ‘Mrs. Tick,’ by the end of her account, becomes the ‘mother of nearly four thousand healthy ticklets’ and the ‘proud grandmother of 8 million bouncing youngsters,’ who are represented by an explosion of wiggly dots on the screen-within-the-screen….The Charge of the Tick Brigade concludes with a map of the Southern quarantine line, indicating areas where tick infestation was still problematic….(The USDA made updated maps as progress was made and inserted those into prints used at later screenings.) The final intertitle implores viewers living in those regions to ‘Dip that tick now. The United States Department of Agriculture will be glad to show you how without charge….’" p. 34

Zwarich. J. (2009). The bureaucratic activist: Federal filmmakers and social change in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s tick eradication campaign. The Moving Image, 9(1), 19-53. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41167316.

The following images are stills from this silent film. The entire video is available for viewing and/or download at the National Archives and Records Administration:

Max Fleischer, Bray Studios, Inc., & U.S. Department of Agriculture. (1919). The charge of the tick brigade. National Archives and Records Administration. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/7102.

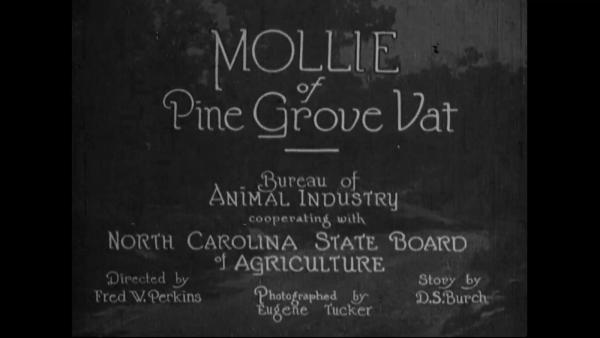

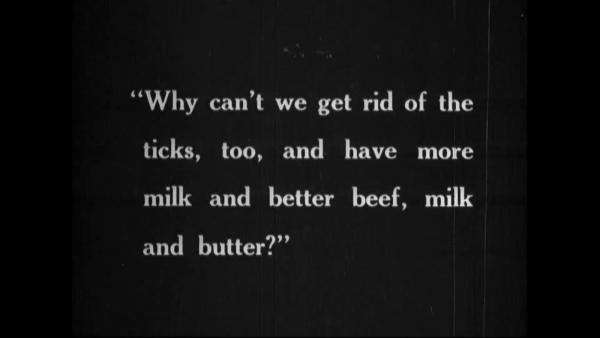

Mollie of Pine Grove Vat

"On October 1922, department photographer Eugene Tucker journeyed with Motion Picture Chief Perkins to the town of Washington, North Carolina, to spend a planned seven to ten days shooting amateur actors on a working farm. The resulting film mirrors the style and narrative arc of popular prewar heroine serials like the Perils of Pauline (1914), but it combines this with a generic local aesthetic that emphasizes problems, locations, and characters familiar to the film’s rural audiences. The intertitles are peppered with common objections to the eradication program, voiced by Pine Grove citizens, which the film then attempts to counter….According to agriculture department reports, Mollie of Pine Grove Vat enjoyed great success among audiences in the South. In 1923—after several months of motion picture truck exhibition throughout southern Georgia—the department issued a press release that claimed the film had “made friends of the dipping vat” in formerly hostile areas and on one occasion had even changed the mind of a man who had threatened to blow up the motion picture truck!48 In its annual report, the BAI [Bureau of Animal Industry] singled out the film as having ‘been especially useful in preliminary tick eradication work.’"pp 40; 44

Zwarich. J. (2009). The bureaucratic activist: Federal filmmakers and social change in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s tick eradication campaign. The Moving Image, 9(1), 19-53. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41167316.

The following images are stills from this silent film. The entire video is available for viewing and/or download at the National Archives and Records Administration:

Bureau of Animal Industry, U.S. Department of Agriculture & North Carolina State Board of Agriculture (1922). Mollie of Pine Grove Vat. National Archives and Records Administration. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/7169.

The Tick Riders & The Quarantine Zone

“USDA and its partners worked together to eradicate the disease from the country by 1943, except for a permanent quarantine area along the Texas/Mexico border, where the ticks that carry this disease are still found. Mexico continues to find babesiosis, so this buffer zone plays an important role in keeping ticks from spreading the disease back into the United States.”

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) (2018). Protecting U.S. cattle from fever ticks: Cattle fever tick eradication program and treatment options. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/animal_diseases/tick/downloads/bro-cft-treatment-options.pdf.

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) (2018). Protecting U.S. cattle from fever ticks: Cattle fever tick eradication program and treatment options. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/animal_diseases/tick/downloads/bro-cft-treatment-options.pdf

“In 1906, the Cattle Fever Tick Eradication Program (CFTEP) was initiated with a focus on cattle as primary hosts for cattle fever ticks….In 1938, a permanent quarantine or "buffer" zone (perimeter shown in red) was created along the U.S./Mexico border to prevent cattle tick reintroduction into the United States. The zone is defined by various public roads, running parallel to the Rio Grande for approximately 580 miles and ranging up to 10 miles wide….By 1943, the eradication of cattle fever ticks from 14 southern States was declared successful….Although a quarantine zone is in place to eliminate the spread of CFTs, they continue to spread.”

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) (2024, July 16). Highlights of veterinary services' Cattle Fever Tick program Story Map. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/news/stories/cattle-fever-tick-program-highl…

Kammlah, D. (n.d.). A quarantine line was established in 1943 to create a buffer zone along the Texas/Mexico border, from Del Rio to Brownsville, to protect the southern United States against spread of ticks from Mexico. Agricultural Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.ars.usda.gov/oc/images/photos/jun06/d515-1/.

“The Permanent Quarantine “Buffer” Zone, also known as the Systematic Area (SA), serves as the buffer between Mexico, where ticks are endemic, and the rest of the fever tick-free United States, called the Free Area. The SA consists of over a half million acres, stretching from the Gulf of Mexico near Brownsville, Texas, to Amistad Dam north of Del Rio, Texas.”

Texas Animal Health Commission (2017). Frequently asked questions: Cattle Fever Ticks. https://www.tahc.texas.gov/news/brochures/TAHCBrochure_FeverTickFAQ.pdf.

Duhaime, R.(n.d.). The Rio Grande from a Border Patrol helicopter near Del Rio, Texas. The United States is to the left and Mexico is to the right. In many places, the river is shallow and can be easily crossed by animals that may carry ticks. Agricultural Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Image Number D514-1. https://www.ars.usda.gov/oc/images/photos/jun06/d514-1.

The Cattle Fever Tick Eradication Program: How It Works

Bauer, S. (n.d.). Entomologist Elmer Ahrens (left) and animal caretaker Adolfo Pena inspect for cattle fever ticks. Image Number K5441-1. Agricultural Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.ars.usda.gov/oc/images/photos/k5441-1/.

“USDA or TAHC [Texas Animal Health Commission] inspects all livestock within the permanent quarantine zone for ticks every year. USDA or TAHC inspectors also must treat, inspect, and certify all cattle as tick-free before they can move out of the quarantine zone to prevent ticks from spreading.

In addition, USDA and TAHC set up temporary quarantines as needed if the ticks are found outside of the permanent quarantine zone. These animals must also be treated and inspected before leaving quarantine. These treatments are discussed below. There are separate rules for releasing the temporary quarantines and returning the land to normal status; if you have questions about that process, please contact USDA or TAHC officials.

To help combat the spread of ticks, USDA also has a cadre of “tick riders,” or mounted patrol inspectors, who ride along the Texas/Mexico border looking for livestock that stray across the border. They round up any stray livestock they find, inspect them for ticks, and then treat them before returning them to their owners.”

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) (2018). Protecting U.S. cattle from fever ticks: Cattle fever tick eradication program and treatment options. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/animal_diseases/tick/downloads/bro-cft-treatment-options.pdf.

More information on the programs to combat and investigate the Cattle Fever Tick and Bovine Babesiosis is available from:

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS)

U.S. Department of Agriculture

4700 River Road

Riverdale, MD 20737

https://www.aphis.usda.gov/news/stories/cattle-fever-tick-program-highlights-story-map

Knipling-Bushland U.S. Livestock Insects Research Laboratory

Agricultural Research Service: Plains Area

U.S. Department of Agriculture

2700 Fredicksburg Road

Kerrville, TX 78028

https://www.ars.usda.gov/plains-area/kerrville-tx/knipling-bushland-us-livestock-insects-research-laboratory/

Texas Animal Health Commission

State of Texas

2105 Kramer Lane

Austin, Texas 78758

https://www.tahc.texas.gov/animal_health/feverticks-pests/

-- Emily Marsh, Ph.D., MLS

The U.S. Department of Agriculture published many materials documenting Texas Cattle Fever and the means of its transmission and control. Here is a sample of these publications held by the National Agricultural Library.

Smith, T. & Kilborne, K.L. (1893). Investigations into the nature, causation, and prevention of Texas or southern cattle fever. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Bureau of Animal Industry. Bulletin Number 1. https://archive.org/details/bullbai001.

"Conclusions

(1) Texas cattle fever is a disease of the blood, characterized by a destruction of red corpuscles. The symptoms are partly due to the ansemia produced; partly to the large amount of debris in the blood, which is excreted with difficulty, and which causes derangement of the organs occupied with its removal.(2) The destruction of the red corpuscles is due to a microorganism or micro-parasite which lives within them. It belongs to the protozoa and passes through several distinct phases in the blood.

(3) Cattle from the permanently infected territory, though otherwise healthy, carry the micro-parasite of Texas fever in their blood.

(4) Texas fever may be produced in susceptible cattle by the direct inoculation of blood containing the micro-parasite.

(5) Texas fever in nature is transmitted from cattle which come from the permanently infected territory to cattle outside of this territory by the cattle tick (Boophilus bovis).

(6) The infection is carried by the progeny of the ticks which matured on infected cattle, and is inoculated by them directly into the blood of susceptible cattle."

Mohler, J.R. (1905). Texas fever: Otherwise known as tick fever, splenetic fever or southern cattle fever, with methods for its prevention. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Bureau of Animal Industry. Bulletin Number 78. https://archive.org/details/bullbai078

"Texas fever, a very serious obstacle to the development and prosperity of the cattle industry of the South, has been pretty thoroughly understood since the investigations and discoveries made by Smith and Kilborne and published in 1893 as Bulletin No. 1 of the Bureau of Animal Industry. Their work showed conclusively that the cause of the disease was an intracorpuscular parasite (one living within the blood cells), the intermediate stage of the development of which occurred in the cattle tick, thus making this tick the indirect but absolutely essential factor in the natural production of the disease."

Hunter, W.D. & Hooker, W.A. (1907).

Information concerning the North American fever tick: With notes on other species. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Bureau of Entomology, Bulletin Number 72. https://archive.org/details/informationconce72hunt

"It is safe to state that no more important problem than the eradication of the cattle tick confronts the farmers of any country. Not only the cattle-raising industry, but the whole economic condition of a large section of country is affected. The tick, without any but the most limited power of locomotion, and for all practical purposes dependent upon cattle for its existence and dissemination, presents a problem in eradication of a hopeful nature. Cattle are under the control of man. Therefore, the problem is quite different from that involved with other pests, like the boll weevil, which by flight spread over large areas of land. In the one case absolute eradication is possible and in the other it is out of the question. In fact the possibility of the total extermination of the tick in this country is by no means visionary. It was foreseen originally, probably, by Dr. Cooper Curtice, who wrote as follows in 1896: 'I look most eagerly for the cleansing of even a certain portion of the infected territory under the direct intention of man, for it opens the way to pushing the tick back to the Spanish Isles and Mexico, and liberating cattle from disease and pests and the farmer from untold money losses. Let your war cry be, 'Death to the ticks.'"

Curtice, C. (1912). Progress and prospects of tick eradication. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Bureau of Animal Industry. Circular Number 187. https://archive.org/details/CAT31283933

"The southern portion of the United States has long been afflicted by the presence of the cattle tick Margaropus annulatm. These ticks spread the infection of the disease known as Texas fever of cattle and often infest cattle so numerously as to stunt their growth and seriously affect their condition. Their presence necessitates a quarantine under which cattle from the infected regions may be shipped to other parts of the country only under certain restrictions and for immediate slaughter. The ticks also largely prevent the introduction and breeding of fine stock. The damage and losses caused by these parasites are enormous, being estimated at from $40,000,000 to $200,000,000 a year.

Systematic cooperative work by the Federal Government and the affected States for the eradication of these ticks has now been in progress nearly five years, and it is opportune to pause and look over the field to ascertain what has been accomplished, what obstacles have been encountered, and what may be done to assist in the further prosecution of the work."

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (1916). Cattle ticks worse than a wound. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://archive.org/details/CAT31413577/page/n2/mode/2up

"If one of your steers or dairy cows got a bad cut and was bleeding nearly a quart of blood a day, you’d do something about it in a hurry. You’d know that such loss of blood would weaken the animal, prevent its putting on weight, and, in the case of the cow, you’d soon see the milk flow fall off. If you couldn’t handle the wound yourself you’d think it a good investment to pay a veterinarian from 50 cents to $1, or more, to stop the bleeding.

Ticks have the same effect on a steer or a cow as such a wound, but the difference is that you don’t see the blood dripping because it flows into the tick. Every tick bite is a tiny wound on the animal through which blood is constantly being drawn. These tiny wounds and the drawing of this blood irritate the animal and weaken it just the same as the wound. The wound, of course, may become infected and make the animal very sick, but the tick in addition to causing blood to flow may give the animal Texas fever and even kill it."

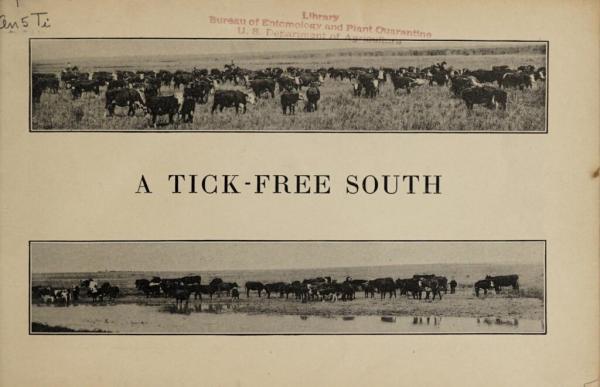

Bureau of Animal Industry. U.S. Department of Agriculture (1917). A tick-free south. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://archive.org/details/CAT10683253

"The cattle tick is being stamped out in the South.

On thousands of farms, where it once feasted on unthrifty scrubs, there are now pure-bred bulls and grade herds of beef and dairy cattle, grazing in security and turning their owners’ feed into flesh and milk untaxed by the toll of blood the tick levies on its victims. The change that the elimination of the pest can bring is shown in these pictures. Their like can be seen in any of the tick-freed areas. These areas are growing in number and size each year. Already many States are absolutely free, and the total eradication of the tick is now only a matter of determination on the part of those who still suffer from it. A trifling investment of money and trouble will release any county from the handicap under which southern farmers have always labored."

Ellenberger, W.M. (1920). Cattle-fever ticks and methods of eradication. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Farmers’ Bulletin, Number 1057. https://archive.org/details/CAT31101021

"The eradication of the cattle tick from the Southern States is a problem of prime importance to the agricultural welfare of the entire country.

The elimination of the tick will give a very great impetus to the cattle and dairy interests, especially of the South, where agriculture will be placed on a more scientific and profitable basis.

Although the eradication of the tick will be of greatest advantage to the States in which ticks are found, the benefits will be enjoyed also by all other sections. In consequence the problem, in large measure, is one of national importance.

A number of publications on the cattle tick, its habits, and methods of eradication have been issued by the United States Department of Agriculture and by various investigators in the Southern States. This bulletin, prepared for the use of farmers, stock-men, and other interested persons, brings together, from the various sources, practical and useful information regarding the tick and its eradication."

Bureau of Animal Industry. U.S. Department of Agriculture (1927). The Story of the cattle-fever tick: What every southern child should know about cattle ticks. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Miscellaneous Publication Number 2. https://archive.org/details/storyofcattlefev02unit

"Dear Children of the South:

This story book tells you why so many cows and steers and calves in the South get sick and die. I know that you would rather see fat, healthy cattle than thin and sick ones. Most cattle that die of sickness in the South die from the bites of cattle-fever ticks. The ticks carry tick fever from sick animals to healthy ones. Other names for tick fever are 'redwater' and 'murrain.' Some cattle that the ticks bite do not die, but the fever ticks prevent them from giving as much milk or growing into as good meat animals as they otherwise would.

This story book tells how to get rid of these robber ticks that bite cattle and suck their blood. The best way to fight ticks is to build dipping vats and make the cattle swim through a medicine that kills the ticks. The medicine doesn't hurt the cattle at all. In many counties people have got rid of ticks that way and now are sending to market the milk and meat that the ticks used to steal.

Get your father and mother to read this story book and to help fight cattle-fever ticks. I hope you will like this little book and show it to your friends."

MacKellar, W.M. (1929). How to get the last tick: Observations resulting from active field experience in tick eradication. Bureau of Animal Industry. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://archive.org/details/CAT10515325

"The results obtained in eradicating cattle ticks from the infested areas of the United States have clearly established the fact that it is possible and practicable to eliminate this pest permanently from any section of the country. This is true whether the infested cattle are under fence or on open range, or whether the infested locality is rough, swampy, wooded, or otherwise. The large area that has been freed and remains tick-free is positive proof of the value of this work which, more than any other factor, is making possible the establishment of a growing and profitable cattle industry in the South."

Mohler, J.R. (1930). Tick fever. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Farmers’ Bulletin, Number 1625. https://archive.org/details/CAT87203791

"This publication deals with many questions that arise concerning tick fever and the eradication of the cattle tick which transmits this disease. The difference between fever ticks and the harmless ticks often found on cattle and other animals is described and illustrated.

The purpose of the bulletin is to inform livestock owners and the public, especially in the Southern States, regarding the nature of tick fever, the scientific work underlying present methods of eradication, and the benefits to be derived from cooperating with county, State, and Federal authorities in ridding the country of cattle ticks and the disease which they carry."

References

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) (2018). Protecting U.S. cattle from fever ticks: Cattle fever tick eradication program and treatment options. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/animal_diseases/tick/downloads/bro-cft-treatment-options.pdf.

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) (2024, July 16). Highlights of veterinary services' Cattle Fever Tick program Story Map. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/news/stories/cattle-fever-tick-program-highlights-story-map.

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. (APHIS) (2020, June 2). Cattle Fever Tick control barrier. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://tinyurl.com/mr2792rr.

Bauer, S. (n.d.). At the Rio Grande, Robert Rodriguez (left) and Horico Garza, of USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, search for livestock that may be carrying ticks. Cattle fever ticks have been eradicated from this country since 1943 except for a narrow strip along the border. Image Number K5439-20. Agricultural Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.ars.usda.gov/oc/images/photos/k5439-20.

Bauer, S. (n.d.). Entomologist Elmer Ahrens (left) and animal caretaker Adolfo Pena inspect for cattle fever ticks. Image Number K5441-1. Agricultural Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.ars.usda.gov/oc/images/photos/k5441-1/.

Bauer, S. (2002). After a 36-year campaign, cattle fever ticks were finally declared eradicated from the United States in 1943. Today, the only remaining area where these ticks are found is a narrow strip of land along the Texas-Mexico border that has been quarantined since 1938. These cattle are going through a tick treatment bath at an APHIS facility in McAllen, Texas. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cattle_tick_treatment.jpg.

Bureau of Animal Industry, U.S. Department of Agriculture (1915). Quarantine for Texas fever of cattle: December 1, 1915. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://archive.org/details/CAT31412086.

Bureau of Animal Industry, U.S. Department of Agriculture, North Carolina State Board of Agriculture (1922). Mollie of Pine Grove Vat. National Archives and Records Administration. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/7169.

Busch, J. D., Stone, N. E., Nottingham, R., Araya-Anchetta, A., Lewis, J., Hochhalter, C., Giles, J. R., Gruendike, J., Freeman, J., Buckmeier, G., Bodine, D., Duhaime, R., Miller, R. J., Davey, R. B., Olafson, P. U., Scoles, G. A., & Wagner, D. M. (2014). Widespread movement of invasive cattle fever ticks (Rhipicephalus microplus) in southern Texas leads to shared local infestations on cattle and deer. Parasites & Vectors, 7, 188. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-188.

Cooper Curtice (n.d.). Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.nal.usda.gov/exhibits/speccoll/exhibits/show/parasitic-diseases-with-econom/item/8292

Dip that tick (n.d.). National Museum of American History. The Smithsonian Institution. Record ID: nmah_502069. https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/object/nmah_502069.

Duffy, J. (1974). A history of public health in New York City: 1866-1966. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Duhaime, R.(n.d.). The Rio Grande from a Border Patrol helicopter near Del Rio, Texas. The United States is to the left and Mexico is to the right. In many places, the river is shallow and can be easily crossed by animals that may carry ticks. Agricultural Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Image Number D514-1. https://www.ars.usda.gov/oc/images/photos/jun06/d514-1.

Effects of ticks on cattle (1913). Florida Memory. State Library and Archives of Florida. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/1357.

Emrich, J.S. & Richter, C. (2018). A brief history of bovine immunology in Texas. American Association of Immunologists Newsletter, March/April, 62-65. https://www.aai.org/About/History/History-Articles-Keep-for-Hierarchy/A-Brief-History-of-Bovine-Immunology-in-Texas.

Erlandson, E.M. (2012). Cattle plague in NYC: The untold campaign of America’s first board of health, 1868. Unpublished manuscript. http://hdl.handle.net/1794/12138.

Forbes, E. (1868). The Cattle Plague. Harper’s Weekly, XII(609), 552-553. https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv12bonn.

Frederick L. Kilborne (n.d.). Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.nal.usda.gov/exhibits/speccoll/exhibits/show/parasitic-diseases-with-econom/item/8199

Fritz, A.L. (2014). This is the dip vat used to treat Mexican cattle for cattle fever ticks to prevent their spread into the U.S. at the newly built U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Animal Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) Livestock Contingency Inspection Facility along the Mexican border in Douglas, AZ. https://www.flickr.com/photos/usdagov/15581737481.

Garry, F. (2008). Miscellaneous infectious diseases. In Divers, T.J. & Peek, S.F. (Eds.), Rebhun’s Diseases of Dairy Cattle, second edition, pp. 606-639. Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4160-3137-6.X0001-5.

Giles, J.R., Peterson, A.T., Busch, J.D., Olafson, P.U., Scoles, G.A., Davey, R.B., Pound, J.M., Kammlah, D.M., Lohmeyer, K.H., & Wagner, D.M. (2014). Invasive potential of cattle fever ticks in the southern United States. Parasites & Vectors, 7, 189. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-189.

Graham, O.H. & Hourrigan, J.L. (1977). Eradication programs for the Arthropod parasites of livestock. Journal of Medical Entomology, 13(6), 629–658. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/13.6.629.

Grandin, T. (n.d.). Explanation of dip vat entrance design. https://www.grandin.com/design/blueprint/enter.dipvat.html.

Graybill, H.W. (1911). Directions for constructing a vat and dipping cattle to destroy ticks. Bureau of Animal Industry Circular 183. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://archive.org/details/CAT31283812.

The great abattoirs at Communipaw (1866). Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, November 17, 1866, XXIII(581), 135. https://archive.org/details/sim_leslies-weekly_1866-11-17_23_58.

Hillers, J.K. (1929). St. Mary’s River Bridge on U.S. 17 at Georgia. Florida State line. Cattle tick and Mediterranean fruit fly quarantine crew at work. Department of Commerce. Bureau of Public Roads. National Archives and Records Administration. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/205739446.

Hillers, J.K. (1929). St. Mary’s River Bridge on U.S. 17 at Georgia-Florida state line: Cattle tick quarantine inspector at work. Department of Commerce. Bureau of Public Roads. National Archives and Records Administration. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/205739448.

Hunter, W.D. & Hooker, W.A. (1907). Information concerning the North American fever tick: With notes on other species. Bureau of Entomology. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Bulletin Number 72. https://archive.org/details/informationconce72hunt.

Kammlah, D. (n.d.). A quarantine line was established in 1943 to create a buffer zone along the Texas/Mexico border, from Del Rio to Brownsville, to protect the southern United States against spread of ticks from Mexico. Agricultural Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.ars.usda.gov/oc/images/photos/jun06/d515-1/.

Levy, M.G. & Ristic, M. (1980). Babesia bovis: Continuous cultivation in a Microaerophilous stationary phase culture. Science, 207(4436), 1218-1220. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7355284.

Loughlin, E. (1948). Kill those pests! Livestock insects cause half billion dollar loss yearly in food, feed, fiber, and hides: Ask your county agent how to stop it. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://archive.org/details/CAT31069222.

Max Fleischer, Bray Studios, Inc., & U.S. Department of Agriculture. (1919). The charge of the tick brigade. National Archives and Records Administration. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/7102.

Mosqueda, J., Olvera-Ramirez, A., Aguilar-Tipacamu, G., & Canto, G. J. (2012). Current advances in detection and treatment of babesiosis. Current Medicinal Chemistry, 19(10), 1504–1518. https://doi.org/10.2174/092986712799828355.

National Park Service (1980). Major cattle trails 1866-1890. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cattle-trails.jpg

Norgaard, V.A. (1898). Cattle dipping, experimental and practical. In Yearbook of the United States Department of Agriculture 1898, pp. 453-472. https://archive.org/details/yoa1898/page/453.

Nyangiwe, N., Yawa, M., & Muchenje, V. (2018). Driving forces for changes in geographic range of cattle ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) in Africa: A review. South African Journal of Animal Science, 48(5), 829-841. http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/sajas.v48i5.4.

Olmstead, A.L. & Rhode, P.W. (2015). Arresting contagion: Science, policy, and conflicts over animal disease control. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Qiu, L. (2022, July 23). Meet the canine officers guarding American agriculture. The New York Times, July 24, 2022, Section A, Page 14. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/23/us/politics/beagles-airport-security.html.

Rumsey & Company. (1910). Dipping vat at Circle Ranch, near Queenstown, Alberta. https://archive.org/details/PC009898.

Smith, T. & Kilborne, F.L. (1893). Investigations into the nature, causation, and prevention of Texas or southern cattle fever. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Bureau of Animal Industry. Bulletin Number 1. https://archive.org/details/bullbai001.

Spickler, A.R. (2018). Bovine Babesiosis. College of Veterinary Medicine. Iowa State University. https://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/bovine_babesiosis.pdf.

Swiger, S.L. (2017). Cattle fever ticks. Texas A&M AgriLife Extension. https://entomology.tamu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ENTO-065-Cattle-Fever-Ticks.pdf.

Texas Animal Health Commission (2017). Frequently asked questions: Cattle Fever Ticks. https://www.tahc.texas.gov/news/brochures/TAHCBrochure_FeverTickFAQ.pdf.

Theobald Smith (n.d.). Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.nal.usda.gov/exhibits/speccoll/exhibits/show/parasitic-diseases-with-econom/item/8205

Tidwell, J. (n.d.). Female cattle ticks preparing to lay eggs. These ticks can transmit serious diseases to cattle. Image Number D3532-1. Agricultural Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.ars.usda.gov/oc/images/photos/jan16/d3532-1/.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (1960). Vat for dipping cattle. Miscellaneous Publication Number 832. https://archive.org/details/vatfordippingcat832unit.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (1966). Cattle dipping vat & inspection facility. Miscellaneous Publication Number 1035. https://archive.org/details/cattledippingvat1035unit.

Underwood, W.J., Blauwiekel, R., Delano, M.L., Gillesby, R., Mischler, S.A., & Schoell, A. (2015). Biology and diseases of ruminants (sheep, goats, and cattle). In Fox, J.G., Anderson, L.C., Otto, G.M., Pritchett-Corning, & Whary, M.T. (Eds.) Laboratory Animal Medicine, third edition, pp. 623-694. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-409527-4.00015-8.

William Howard Taft Watching a Cattle Dipping (1909). Oklahoma Historical Society: The Gateway to Oklahoma History. https://gateway.okhistory.org/ark:/67531/metadc230806/m1/1/?q=taft.

Winn, J.E. (2012). Documenting racism: African Americans in US Department of Agriculture documentaries, 1921-42. New York: Continuum.

Zwarich. J. (2009). The bureaucratic activist: Federal filmmakers and social change in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s tick eradication campaign. The Moving Image, 9(1), 19-53. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41167316.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.