The lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus L.) has a long and distinguished history that might surprise those of us who know it only as a humble ingredient of succotash.

The most important member [of the wild bean species group] is P. lunatus, the moon-shaped or the lima bean. Its name does come from the Peruvian capital of Lima, even though perversely it is pronounced 'lime-uh' in English. It is among the largest of beans and for those who were subjected to them in the form of canned limas, the memory of their pasty texture, bitter metallic aftertaste and lurid green color can only evoke the gag reflex. This is a pity, for when fresh or even dried they are among the most pleasant and affable of beans, hulking in proportions, gentle and sweet.

Albala, K. (2007). Beans: A History. New York: Berg, p. 191

This short review addresses the many roles played by the lima bean in culture, cuisine, and agricultural science. It also includes a small sample of the many publications produced by the U.S. Department of Agriculture to document the scientific development of lima beans and also to help farmers establish, grow, and manage this crop.

Lima Bean Iconography

The early history of the lima bean is intertwined in the foodways of two indigenous peoples: those of South and North America, specifically Peru and the American South.

The archeologist Gail Ryser documented the role that lima beans played in the Moche culture in Peru (ca. A.D. 100-800). She observed:

Once considered edible and part of the subsistence base, the lima bean became restricted to use as a status symbol or in ceremonies....Moche elites politically manipulated the lima bean and effectively removed it from regular dietary consumption, while concurrently elevating it through ideological association with the Moche warrior class. It is reasonable to extend the attributes of prestige and privilege associated with the Moche warrior class to both the lima bean and its iconographic counterpart, the bean warrior, which thereafter came to symbolize metaphors of life, death, and rejuvenation. (p. 404)

Ryser, G. (2008). Moche Bean Warriors and the Paleobotanic Record: Why Privilege Beans? In Arqueología Mochica: Nuevos Enfoques, edited by L. J. Castillo, H. Bernier, G. Lockard, and J. Rucabado, pp. 397–409. Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Peru, Lima.

The elevated role of the lima bean as a symbol of both war and eternal life can be seen in the fine art and pottery of the era.

Vessel Depicting the Assault of Bean Warriors

Date: 100 B.C./A.D. 500

Artist: Moche North coast, Peru

The Art Institute of Chicago

Orginal Image: https://www.artic.edu/artworks/91555/vessel-depicting-the-assault-of-bean-warriors

The "Three Sisters," Succotash, and Native Americans

The three sisters (corn, beans, and squash) were the major staples of Native American agriculture, and were always grown together. Corn was the most important staple food grown by Native Americans, but corn stalks also provided a pole for beans to climb and the shade from the corn benefited squash that grew under the leaves. The beans, as with all legumes, provided nitrogen for the corn and squash. Finally, the shade from large squash and pumpkin leaves held moisture in the ground for all three plants. Although other plants such as potatoes, tomatoes, and peppers were cultivated, the three sisters gardens were the backbone of North American Indian agriculture and provided the primary dietary staples of many tribes, and horticulture remains an important part of modern Native American life....Foods of the American South are greatly influenced by Native Americans: grits, cornmeal mush, cornbread, succotash, and fried green tomatoes are all uniquely southern but with Native American origins., p. 174; 176

Park, S., Hongu, N., and Daily III, J.W. (2016). Native American foods: History, culture, and influence on modern diets. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 3, 171-177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jef.2016.08.001

Charleston Muse Succotash 4981(link is external) by Susan Lucas Hoffman. Used in accordance with the Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0) Creative Commons license

The lima bean was a member of the "three sisters" of American Native cuisine and eventually became known as a prime ingredient of the dish called succotash

Succotash, that savory mélange of corn and beans, is a noble dish with a long history. We have 17th-century Native Americans to thank for it; they introduced the stew to the struggling colonial immigrants. Composed of ingredients unknown in Europe at the time, it gradually became a standard meal in the settlers’ kitchens. The name is a somewhat Anglicized spelling of the Narragansett Indian word “msickquatash,” which referred to a simmering pot of corn to which other ingredients were added.

Tanis, D. (2015, August 19). Summer’s Best, All in One Pot. New York Times, Section D, Page 3.

Lima Beans at Mount Vernon

(1793) George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: George Washington to Anthony Whiting, February 3. February 3. [Manuscript/Mixed Material] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/mgw432918/

Lima beans managed to make an appearance at Mount Vernon. George Washington wrote a letter to Anthong Whiting--a master farmer and estate manager for Washington who worked at Mount Vernon from 1790 until 1793--dated February 3, 1793 and contains the following note:

Under cover with this letter you will receive some Lima Beans which Mrs. Washington desires may be given to the Gardener.

The Burpee Company and Getting "Fordhooked"

Burpee's Fordhook Farm

Burpee's Fordhook Farm. W. Atlee Burpee & Co. 1895. Burpee's Farm Annual 1895, Philadelphia, PA. Smithsonian Libraries Original Image: https://library.si.edu/image-gallery/104802

The modern conception of lima beans as a garden staple is owed in part to W. Atlee Burpee and the Burpee Seed Company. As described by their company history,

In 1888, Burpee bought a farm near Doylestown, Pennsylvania, called Fordhook, and began transforming it into what would soon become a world-famous plant development facility....But occasionally he found what he was looking for surprisingly close to home. Such was the case of the first Bush Lima Bean, which he found growing in the garden of a man named Asa Palmer in Chester, Pennsylvania, in 1890. Until then, lima beans had been strictly climbing plants needing poles for support. After cutworms had wiped out Palmer's bean patch one year, he was stacking his poles for winter when he noticed one odd little plant still flourishing. It was definitely a bush rather than a climber, only a foot high, and it had three little pods each containing a single bean. He planted the seeds the following season, and two of them grew into low bushes bearing a generous yield. He then sold the seeds to W. Atlee Burpee. By 1907, the bush lima bean as we now know it had been developed, and it was named The Fordhook . So exceptional are its eating qualities that it has remained a home gardener's favorite to this day. Lima bean aficionados speak of being "Fordhooked".

W. Atlee Burpee & Co. (undated). The Legacy of W. Atlee Burpee. https://www.burpee.com/gardenadvicecenter/get-to-know/the-legacy-of-w.-a...

Fordhook 242

Dr. Robert Emerson Wester of the U.S. Department of Agriculture provided further description of the two main varieties of lima bean: pole and bush.

Two types of lima beans, called butter beans in the South, are grown in home gardens. Most of the more northerly parts of the United States, including the northern New England States and the northern parts of other States along the Canadian border, are not adapted to the culture of lima beans....Both the small- and large-seeded lima beans are available in pole and bush varieties. In the South, the most commonly grown lima bean varieties are Jackson Wonder, Nemagreen, Henderson Bush, and Sieva pole; in the North, Thorogreen, Dixie Butterpea, and Thaxter are popular small-seeded bush varieties. Fordhook 242...is the most popular midseason large, thick-seeded bush lima bean., p. 38

Wester, R.E. (1972) Growing Vegetables in the Home Garden. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Home and Garden Bulletin Number 202.

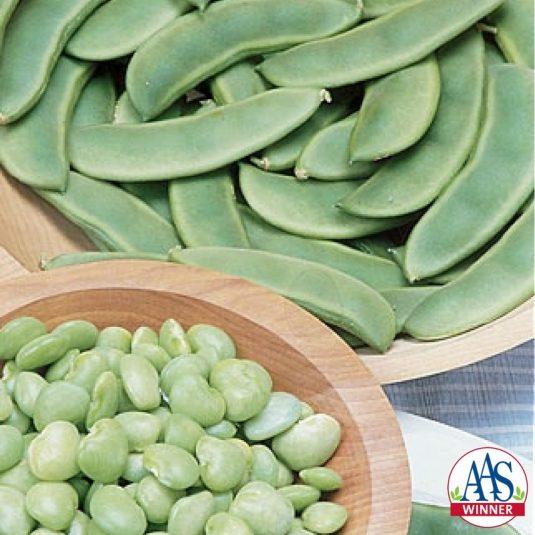

A figure in Growing Vegetables in the Home Garden, (Figure 22, pictured above) illustrates the Fordhook 242 bush lima bean that was selected as a 1945 National All-American Selections winner; Wester was credited as the breeder

In an article published in Southern Seedsman (November 1, 1944), "A Close-Up of Fordhook 242" (p. 14; 28) by Robert E. Wester and Roy Macgruder, the cultivar itself and the procedures used to develop it were described.

Fordhook 242 bush lima bean...was developed by the Agricultural Research Administration of the United States Department of Agriculture and tested extensively in cooperation with numerous experiment stations. It is the result of six generations of selection from a lot of seed of Fordhook type secured by L.C. Curtis of the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station. The heavy early basal set of pods and continuous productivity under high temperature conditions make it an outstanding introduction....In 1942 and 1943 it was grown at 18 experiment stations, and in 1944 it was grown in 22 experiment stations and was entered in the All-America vegetable trials. Such extensive trials, in which it was compared with regular Fordhook and Concentrated Fordhook, have given this new strain or variety a thorough test over the past 3 years....Green shell beans are very slightly smaller than regular Fordhook and have teh same eating quality when fresh, canned, or frozen. They have light green seed coats when immature, fading to greenish cream and light green in color when dry. The orginal seed stock was placed in the hands of commercial growers or lima bean seed for increase under the most favorable conditions. Several of the well-known producers of lima bean seed now have commercial stocks for sale. p. 14; 28

Marketing of Foodhook 242

As stated above, Fordhook 242 was then commercially marketed to the home trade by vendors including Henry A. Dreer and Associated Seed Growers, Inc. , as illustrated in the following advertisements:

Dreer's Novelties and Specialties for 1948. Henry A. Dreer. 1948 Henry G. Gilbert Nursery and Seed Trade Catalog Collection. National Agricultural Library. https://archive.org/details/dreersnoveltiess1948henr/page/n1

Descriptive Catalog of Vegetables for Canning and Freezing. Associated Seed Growers, Inc. 1949 Henry G. Gilbert Nursery and Seed Trade Catalog Collection National Agricultural Library. https://archive.org/details/descriptivecata1949asso_0

Genetic Lineage

The origin of the lima bean has been studied for quite some time. In a 1943 publication Mackie described the plant orginating from the jungles of Guatemala and to have descended into three lines: "(1) the Hopi, or northern branch, (2) the Carib, or West Indies, branch,...and (3) the Inca, or southern, branch."

Mackie, W.W. (1943). Origin, dispersal, and variability of the lima bean, Phaselous Lunatus. Hilagardia, 15(1), p. 3.

More recent scholarship, however "indicates the existence of only two gene pools in lima beans, Mesoamerican and Andean (Baudoin, 1988; Debouck et al., 1989). The Meso american lima bean gene pool extends from the southwestern United States to Argentina and is characterized by small seed size (0.24 to 0.70 g/seed) (Debouck et al., 1989: Maquet et al., 1990). The Andean lima bean gene pool extends from the equator to north of Peru for wild forms and from Colombia to southern Brazil for cultivated forms and is characterized by large seed size (>0.54 g/seed) (Debouck et al., 1989; Maquet et al., 1990; Maquet et al., 1993)."

Nienhuis, J., Tivang, J., Skroch, P., and dos Santos, J.B. (1995). Genetic relationships among cultivars and landraces of lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus L.) as measured by RAPD markers. Journal of the American Society of Horticultural Science, 120(2), p. 300.

The identification of two major gene pools for the lima bean has been maintained by more recent works:

Martínez-Castillo, J., Zizumbo-Villarreal, D., Gepts, P., Delgado-Valerio, P., & Colunga-García Marín, P. (2006). Structure and genetic diversity of wild populations of lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus L.) from the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Crop Science, 46, 1071-1080. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2005.05-0081.

However, Camacho-Perez, et al. observed:

[R]ecent studies indicate the existence of three major gene pools within the species: the Andean (A), Mesoamerican I (MI) and Mesoamerican II (MII), all of which contain wild and domesticated forms.

Camacho-Pérez, L., Martínez-Castillo, J., Mijangos-Cortés, J.O., et al. (2018). Genetic structure of Lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus L.) landraces grown in the Mayan area. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolultion. 65(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-017-0525-1(link is external).

They cite the following to support their argument in favor of these three lines:

Serrano-Serrano ML, Hernandez-Torres J, Castillo-Villamizar G, Debouck DG, Chacón, MI. (2010) Gene pools in wild Lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus L.) from the Americas: Evidences for an Andean origin and past migrations. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 54:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2009.08.028(link is external).

Serrano-Serrano ML, Andueza-Noh RH, Martínez-Castillo J, Debouck DG, Chacón, MI. (2012) Evolution and domestication of Lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus L.) in Mexico: Evidence from ribosomal DNA. Crop Science, 52:1698–1712. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2011.12.0642.(link is external)

Martínez-Castillo J, Camacho-Pérez L, Villanueva-Viramontes S, Andueza-Noh RH, Chacón-Sánchez, MI. (2014) Genetic structure within the Mesoamerican gene pool of wild Phaseolus lunatus (Fabaceae) from Mexico as revealed by microsatellite markers: Implications for conservation and the domestication of the species. American Journal of Botany, 101(5):851–864. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1300412.

USDA Publications on Lima Beans

The U.S. Department of Agriculture published many materials in the twentieth century to document the scientific development of lima beans and also to help farmers establish, grow, and manage this crop. Here is a sample of these publications.

Wester, R.E. (1958) Downy Mildew-Resistant Fordhook Limas

Three green-seeded downy mildew Fordhooks (156, 1556, and 1656) will be tested extensively in the downy mildew areas this year. During the past season (1957) which was unusually hot and dry, they showed less heat resistance than Fordhook 242 but they will set a good crop of pods during the cool weather of late summer and mature their crop of pods during the downy mildew season. These lines resulted from five backcrosses to Fordhook 242. Approximately 40 F2 downy mildew-resistant Fordhooks from six backcrosses to Fordhook 242 are now growing in the greenhouse. There are white and green-seeded types in these families.Although it has been more difficult to develop a high yielding heat-resistant downy mildew-resistant Fordhook than the bay types, definite progress is being made.

--p. 19

Wester, R.E. (1963) Green-Seeded Downy Mildew-Resistant Fordhook Lima Beans

Three new green-seeded downy mildew-resistant Fordhook lima beans(U.S. 561, 861, and 1061) showed considerable promise in Maryland, New Jersey, and Long Island in 1961 and 1962. They resisted downy mildew (Phytophthora phaseoli Thaxt.) strain "A" which in some years causes considerable damage to lima beans in Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and New York. Their yields equalled or exceeded those of Fordhook 242. Plants of the new lines are slightly shorter and more compact than those of Fordhook 242 and have short racemee that produce a heavy crop of pods below the foliage, thus preventing flower drop which often results from excessive heat, drought, wind, and rain. Pods reach prime marketable condition 4 to 6 days later than Fordhook 242 and remain in this condition several days longer. The pods are approximately as long and thick as Fordhook 242 but not quite so wide. The shelled beans are slightly smaller than those of Fordhook 242 and darker green in frozen pack. The quality of the cooked beans is excellent.

--pp. 28-29

Wester, R.E. (1965) Lima Bean Investigations

Downy mildew on the move in 1964. Downy mildew, Phytophthora phaseoli, Thaxt. strain B was observed on September 1,1964, on Thaxter bush lima bean two miles west of Shiloh, New Jersey, which is 10 miles southwest of the Pittsgrove area where this strain was first observed in 1958. It was inactive in 1959 and in 1960 spread slightly north of Pittsgrove and six miles south to six other locations that extended to the Research Center of Seabrook Farms Company at Bridgeton, New Jersey. From 1961 through 1963 this strain did not re-occur in any of the previously mentioned locations.

--p. 49

Wester, R.E. (1967) Introducing Green Seeded Fordhook Bush Lima Beans

Green Seeded Fordhook lima bean (tested under U.S, 86l), which is resistant to downy mildew strain A, was released to lima bean seedsmen in the spring of 1966, This is the first green-seeded Fordhook variety released to the trade.

--p. 28

Corbett, L. C. (1923) Beans. Farmers' Bulletin, Number 289, revised

Lima beans are of very great commercial value, but are not sufficiently appreciated as a table food because it is not generally known that in a dry state they can be used in practically the same manner as are the common beans.

In reality they are richer and more delicate in flavor than the common beans, and can be used in as many different ways. The virtues of these types as green beans need only a passing mention, and their value as an accompaniment of corn in succotash is well known to every consumer of canned goods.

--pp. 16-17

Downy mildew of Lima beans can be recognized by the white, cottony growth which forms in large patches on the pods. It sometimes occurs on the tender shoots and flower parts and occasionally on the leaves. The young branches are distorted, but a profuse fungous growth, such as is found on the pods, does not occur on them. A purplish border separates the dense cottony growth on the pod from the healthy tissue. The fungous threads grow through the pods and into the seed, where the organism may live through the winter. Such seed, if planted, may be a source of the disease the next year. If the pods become diseased while quite young they usually wither and die without producing seed. Downy mildew may cause heavy damage during seasons favorable for the development of the fungus. It is favored by wet weather, cool nights, heavy dews, and fairly warm days. The disease is most prevalent along the Atlantic seaboard, but has been reported inland and from California. It is spread by winds, rains, pickers, and probably by insects and other means.

--pp. 23-24

Of the pole types of white lima beans, the small-seeded Carolina, or Sieva, is probably the most dependable, although its quality is only fair. King of the Garden is a large-seeded variety of high quality, but under many conditions it is less productive than Sieva. Florida Butter is a purple-and-buff speckle-seeded kind popular in the South.

Henderson Bush is the most important dwarf lima; it is the one grown most for canning and as dry baby lima beans. It is a dependable bearer, but only fair in quality. Green-seeded strains of this type are now available. Fordhook and Burpee are favorite large-seeded dwarf kinds of high quality, but they frequently are unproductive under adverse conditions. Early Market and Fordhook 242, two new varieties having medium-sized seeds and high quality, are more productive than Fordhook and Burpee in the middle part of the country.

--p. 25

A good garden adds materially to the well-being of the family by supplying foods that might not otherwise be provided. Fresh vegetables direct from the garden are superior in quality to those generally sold on the market, and in addition are readily available when wanted. As a large number of farmers now use lockers and home freezers, even more of the vegetables from the garden can be utilized than when canning and fall storage were the only means of preservation. This publication, intended for country-wide distribution, gives only general information. Any gardener using it needs also local information, especially on the earliest and latest safe planting dates for vegetables and any special garden practices and varieties that are best for his location. Gardeners may get local information and advice from their State agricultural experiment stations (locations below), agricultural extension services, agricultural colleges, and county agents. Farmers' Bulletin 2000, Home Vegetable Gardening in the Central and High Plains and Mountain Valleys, will be especially useful to gardeners in that part of the United States. More detailed information on most of the crops discussed in this bulletin can be obtained from the United States Department of Agriculture, Washington 25, D. C. It is not the purpose of this publication to go into details of the preservation, use, and storage of vegetables. Publications of the Department cover those subjects.

Wester, R.E. (1972) Growing Vegetables in the Home Garden, Home and Garden Bulletin Number 202

Two types of lima beans, called butter beans in the South, are grown in home gardens. Most of the more northerly parts of the United States, including the northern New England States and the northern parts of other States along the Canadian border, are not adapted to the culture of lima beans. Lima beans need a growing season of about 4 months with relatively high temperature; they cannot be planted safely until somewhat later than snap beans. The small butter beans mature in a shorter period than the large-seeded lima beans. The use of plant protectors over the seeds is an aid in obtaining earlier fruiting of the crop. Lima beans may be grown on almost any fertile, well-drained, mellow soil, but it is especially desirable that the soil be lighttextured and not subject to baking, as the seedlings cannot force their way through a hard crust. Covering with some material that will not bake, as suggested for other beans, is a wise precaution when using heavy soils. Lima beans need a soil somewhat richer than is necessary for kidney beans, but the excessive use of fertilizer containing a high percentage of nitrogen should be avoided. Both the small- and large-seeded lima beans are available in pole and bush varieties. In the South, the most commonly grown lima bean varieties are Jackson Wonder, Nemagreen, Henderson Bush, and Sieva pole ; in the North, Thorogreen, Dixie Butterpea, and Thaxter are popular small-seeded bush varieties. Fordhook 242 is the most popular midseason large, thick-seeded bush lima bean. King of the Garden and Challenger are the most popular large-seeded pole lima bean varieties.

--p. 38

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.