Background and Origins

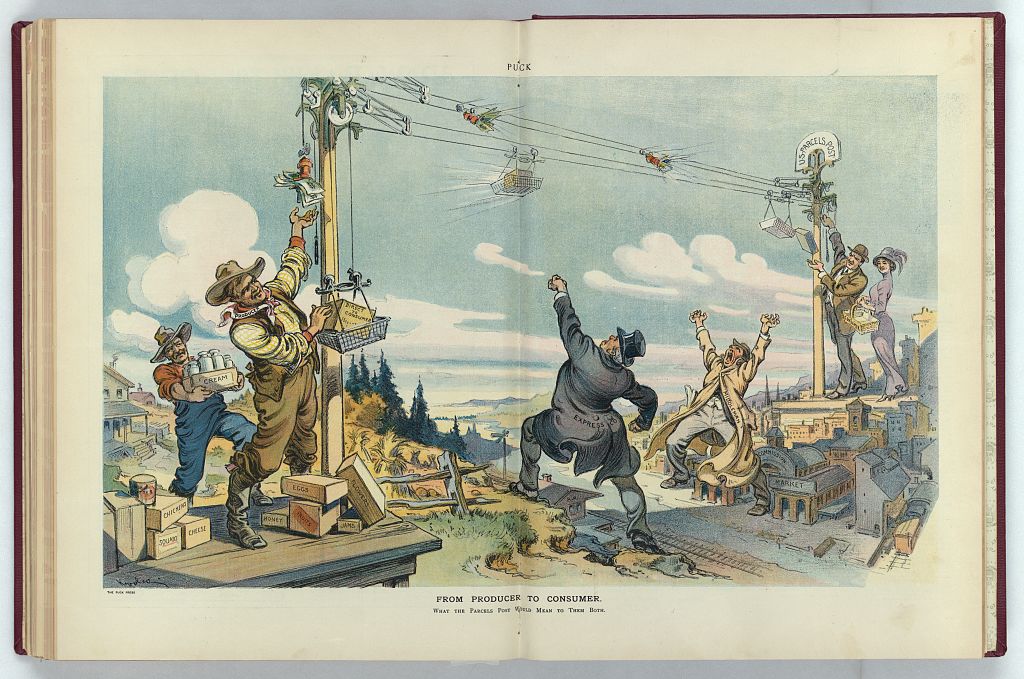

From Producer To Consumer: What The Parcels Post Would Mean to Them Both

Udo J. Keppler (Kep). 1911

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

"Illustration shows two men, one labeled 'Producer,' using a pulley system labeled 'U.S. Parcels Post' to ship a package labeled 'Direct to Consumer' beyond the reach of a man labeled 'Express Co.' straddling a 'R.R.' station and a man labeled 'Middleman' standing in front of a 'Commission Market' to a man labeled 'Consumer' and a woman standing at the other end of the pulley system; the consumer in turn sends payment for the goods received by the same system."

The history of the farm-to-table movement in the 1900s is tied to the expansion of mail service to rural communities. Before the late 1800s the U.S. Postal Service's rural mail delivery was confined to the town postmaster. That meant that farmers did not get mail delivered to their doors. They had to make a trip into town to pick up their mail: winter and summer, rain or shine. A system of direct mail service, Rural Free Delivery (RFD), was first tested in 1896 and made permanent in 1902. RFD made mail delivery to rural citizens' homes possible.

The items eligible to be sent through RFD were limited to envelopes and packages weighing less than 4 pounds, however. While many rural citizens welcomed the ability to get mail delivered to their homes just like their urban counterparts, there was some uneasiness in the larger economic and social worlds over proposals to increase the limit to heavier items. This would open the channel for products to flow directly between seller and consumer, by-passing the then-dominant private shipping companies and merchants who sold items to both rural and urban consumers.

The editorial cartoon shown above, From Producer To Consumer: What The Parcels Post Would Mean to Them Both, illustrates the opposition offered by these two sources: private shipping companies and retailers ("The Middlemen'). Both groups feared a loss of business if packages could be sent through the mail from rural producers to consumers in the cities.

The objections to a systematic program of parcel post delivery were so wide-ranging that it was possible to create an entire monograph to represent both sides of the controversy. In 1913, Edith M. Phelps compiled a set of materials together for an entry in the Debater's Handbook Series. On pages xi-xii of Selected Articles on the Parcels Post (Second and Revised Edition), she outlines some arguments made at the time against such a government service:

I. The present postal deficit would be increased rather than diminished.

A. The cost of the increased service would not be covered by the increased traffic.

1. The government cannot compete successfully with the express companies.

2. There would be a continual demand for more and better equipment.

3. Government undertakings are always more costly than those under private management.

B. The inconsistencies between our present foreign and domestic rates are not as great as has been claimed.

II. The general public would not be benefitted by it.

A. It would have little influence on express rates.

B. It would increase the centralization of wealth, population, and manufactures.

C. The demand for it has been artificially created.

III. Rural communities would be injured by it.

A. Retailers and local dealers would suffer.

1. Orders would be sent direct to manufacturing centers.

2. Mail-order houses would obtain most of the trade.

B. Rural towns and villages would be injured.

1. Trade would be drawn to the larger cities and population would follow.

C. The farmer would not be benefitted.

1. He would not use it nearly as much as has been claimed.

2. The market for his products would be largely destroyed by the removal of population to large cities.

3. The rural parcels post alone would be merely an entering wedge.

In spite of these objections based on fear of business loss, cultural corruption of the "pure" countryside, and runaway government spending, on January 1, 1913 the weight limit of packages accepted by the U.S. Postal Service was increased and Parcel Post was made official. In the words of the cartoonist Udo J. Keppler, "Mount Middleman [was] no longer an insurmountable barrier between producer and consumer."

The Opening Of The Parcels Post Tunnel, January 1, 1913:

Mount Middleman is no longer an insurmountable barrier between producer and consumer

Udo J. Keppler (Kep). 1913

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

"Illustration shows that a freight train has departed a railroad station labeled 'Producer' in the countryside and is passing through a tunnel labeled 'Parcels Post Tunnel' in a mountain labeled 'Mount Middleman' that has the figure of a man on its side; the front of the train has emerged on the city-side of the mountain and is headed toward a station labeled 'Consumer' where a crowd of people are anxiously waiting."

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.